Oscar Wilde’s satirical wit and critique of late Victorian society are well-known, but what is often overlooked is his vision of a radically different, more just society—one that he not only believed was possible but also worth striving for. In his political essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism, Wilde laid out his political ideals, arguing for a world where individual freedom and creativity could flourish free from the constraints of private property and capitalist exploitation. One of Wilde’s most famous—and often misquoted—lines appears in this essay: “To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all.” This encapsulates his belief that modern life, under capitalism, stifles true living and creativity.

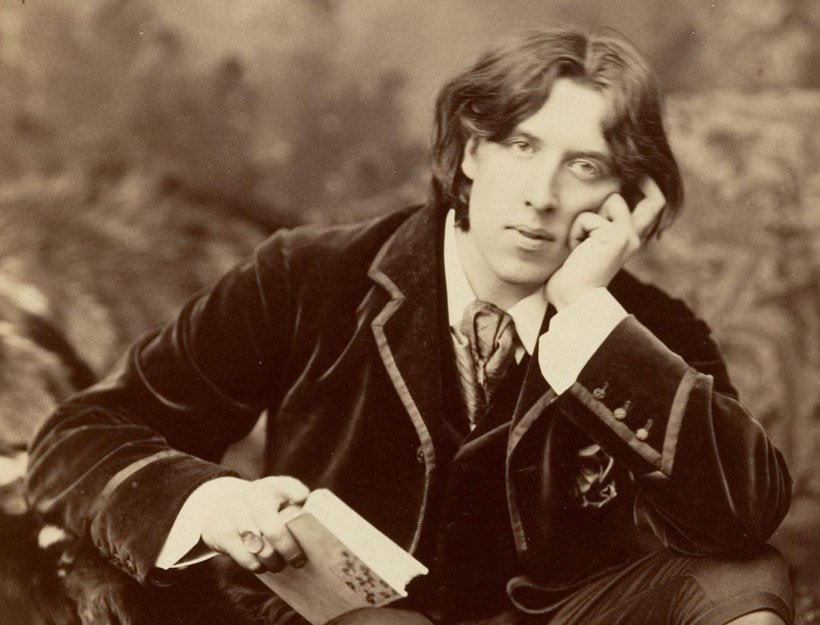

Born in Dublin in October 1854, Wilde was raised in a household that was both intellectually vibrant and politically engaged. His father, William Wilde, was a respected surgeon, and his mother, Jane Wilde, known by the pen name Speranza, was a passionate Irish nationalist and writer. Jane Wilde was deeply involved in the political movements of the time, particularly the Irish nationalist cause, and she encouraged her son to develop his own political awareness. The Wilde home was a meeting place for radical thinkers and activists, including figures from the Young Ireland movement, which had sought to break free from British rule in the mid-nineteenth century. Through his mother, Wilde was exposed to the ideas of revolution and national independence, though he would later find his own path in terms of political thought.

Wilde’s intellectual inheritance was a mixture of radical republicanism and a fascination with aestheticism, a philosophical movement that emphasized beauty, art, and individual expression over utilitarian concerns. While Wilde initially sympathized with the nationalist fervor of the Young Irelanders, his later political views would diverge significantly from traditional Irish republicanism. He spent time in America in 1881, where he lectured on aestheticism, but also stirred controversy with remarks praising the Confederacy and linking Irish struggles with those of the South during the American Civil War. His comments—despite their problematic nature—reflected Wilde’s tendency to shape his views to suit the audiences he addressed. In the case of his admiration for the Confederacy, Wilde’s remarks were more about aligning himself with a form of separatism and autonomy that resonated with his own early sympathies for Irish independence.

Wilde’s more concrete political ideas took shape during his time in London in the 1880s, where he became a prominent figure in intellectual and social circles. As editor of The Woman’s World magazine, he published articles on women’s suffrage, advocating for greater gender equality and decrying the social structures that perpetuated inequality between the sexes. Wilde’s magazine also championed progressive voices, such as feminist writer Olive Schreiner, and he used his platform to call for a more just and equitable society.

Despite his more liberal inclinations, Wilde’s political views were not easily aligned with mainstream ideologies. His signature essay, The Soul of Man Under Socialism, expressed his growing admiration for anarchist ideas, particularly those of Peter Kropotkin, whom Wilde read extensively. In this essay, Wilde criticized the capitalist system that, in his view, reduced individuals to mere cogs in the machine of industry. He proposed a radical rethinking of society in which private property would be abolished and people would be free to pursue personal creativity and fulfillment. For Wilde, socialism was not merely about economic redistribution; it was about freeing individuals from the drudgery of wage labor, allowing them to live fully and authentically.

Wilde’s vision was not a call for a specific political program, but rather for a fundamental transformation in the way society viewed work, leisure, and human potential. He rejected the conventional understanding of socialism, which was often tied to Marxist ideas of class struggle, in favor of a more individualistic and anarchistic approach. According to Wilde, true socialism would create a society where individuals were not defined by their economic roles, but were free to express themselves through art, culture, and personal development. He famously wrote, “With the abolition of private property, we shall have true, beautiful, healthy individualism. Nobody will waste his life in accumulating things, and the symbols for things. One will live. To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all.”

Although Wilde’s vision of socialism was steeped in idealism and philosophical abstraction, it reflected his deep dissatisfaction with the way modern society crushed the spirit of the individual. He critiqued charity as well, arguing that it merely addressed the symptoms of societal ills without tackling their root causes—the capitalist system that reduced people to mere objects of charity rather than fully realized human beings.

Despite the radical nature of his ideas, Wilde’s essay was published at a time when his personal life was in turmoil. Just five days after his conviction for “gross indecency” in 1895, Wilde’s The Soul of Man Under Socialism was printed, albeit in a small, limited run. In a sense, its release was a final statement from Wilde—one of defiance in the face of his personal ruin. His imprisonment would mark the end of Wilde’s literary career in England, but it also produced some of his most poignant and introspective work, including the famous letter De Profundis, written to his former lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, from prison. The letter reveals Wilde’s tortured psyche, but also his determination to remain true to himself in the face of immense suffering.

After his release from prison in 1897, Wilde lived in exile in France under the name Sebastian Melmoth. His later years were marked by personal hardship, but also by the loyalty of his friend and former lover, Robbie Ross, who ensured Wilde’s continued publication and legacy. Ross also arranged for Wilde’s tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery, a monument that became a site of pilgrimage for admirers of Wilde’s wit and subversive genius. The inscription on the tomb, which includes the famous lines “And alien tears will fill for him / Pity’s long-broken urn,” speaks to the tragic yet heroic quality of Wilde’s life, a life that ultimately defied the conventions of both society and his time.

Wilde’s reputation as a satirist, playwright, and wit has endured, but his political writings, particularly The Soul of Man Under Socialism, offer a rich vein of thought on the possibility of a different kind of society—one where the human spirit is liberated from the constraints of materialism and exploitation. His critique of the social order remains as relevant today as it was in the 1890s, offering a timeless reminder of the need to live, not just exist. In the decades following his death, Wilde’s work has inspired generations of thinkers, artists, and activists, not only in Ireland but around the world, challenging the idea that any form of oppression—be it political, economic, or cultural—can limit the potential of the human soul.