Growing Up in the Cost of Living Crisis

Young people in Britain are working harder than ever yet falling further behind every year.

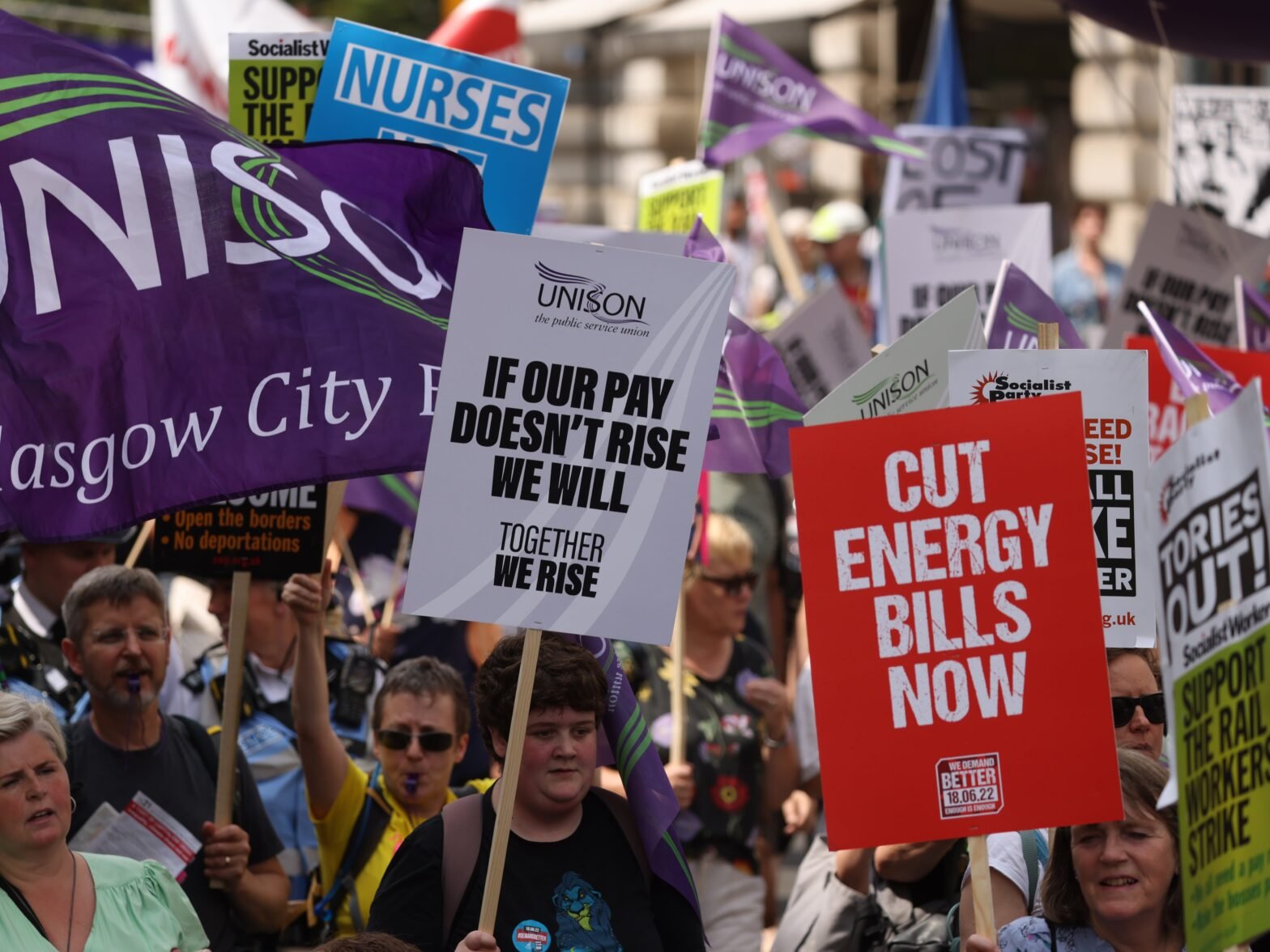

Rising costs and stagnant wages have turned financial independence into a privilege rather than a milestone. For millions of individuals under thirty, the cost of living crisis has reshaped what it means to be young in the United Kingdom. What once marked progress, such as moving out and starting a career or even saving for a home, now feels increasingly out of reach.

The figures are striking. Average private rent in the United Kingdom has risen by more than eight percent in a single year, while real wages have barely grown in a decade. Inflation continues to erode the value of pay and energy bills remain high despite government intervention. For young workers, especially those beginning their careers or burdened with student debt, these pressures feel more than just economic. They function as structural barriers to independence.

The Everyday Struggles Facing Young People

Across the country, the cost of living crisis has exposed how fragile financial stability has become. Housing costs continue to climb, energy bills remain well above pre pandemic levels and the price of food rises faster than wages. Young people, many of whom entered the workforce during a period of economic uncertainty, are among those who are hit the hardest.

Graduates leave university with significant debt, only to enter a job market defined by insecurity. In cities like London and Manchester rent takes up more than a third of average income, making it nearly impossible to save for a deposit. Those who move outside major cities often face fewer career opportunities and lower pay.

The rise of the gig economy has only deepened this instability. While it provides flexibility, it often means unpredictable hours and a lack of benefits. This new landscape of work has left many young people without the financial foundations their parents once took for granted.

Why Wages Do Not Cover the Basics

The link between effort and reward has weakened. Young workers entering the job market today earn less in real terms than their counterparts a decade ago, while the cost of essentials has risen sharply. Even as the minimum wage increases each year, inflation moves faster therefore leaving real income stagnant.

Many young people are trapped in low paid sectors such as hospitality, retail and service industries where progression is slow and job security scarce. Graduates too often accept roles below their skill level simply to make ends meet. The promise that education would open doors now feels hollow when the jobs available cannot support a basic standard of living.

This economic imbalance has broader implications. When young workers cannot afford to build savings or invest in the future, consumer confidence weakens and productivity suffers. The country risks creating a generation that works hard but never gets ahead, a generation whose potential is wasted.

How the Crisis Is Changing Young Lives

Financial strain is shaping more than budgets. It is reshaping lives. Surveys by the Resolution Foundation show that a growing number of young adults delay moving out, pursuing further study or starting families because of financial pressures. What used to be ordinary milestones are now luxuries.

The mental toll is significant. Anxiety, burnout and feelings of hopelessness are increasingly common among those trying to balance rising costs with stagnant pay. Many describe feeling trapped, unable to plan beyond the next month. The sense of progress that once defined early adulthood has given way to frustration and fatigue.

Social mobility, long considered a defining feature of British society, appears to be faltering. For the first time in modern history, young people do not expect to be better off than their parents. That loss of optimism may prove one of the most lasting damages of the crisis.

Building a Fairer Foundation

The government has taken steps to ease the crisis, but most measures have been short term. Energy rebates and temporary payments have offered brief relief, yet have not addressed the deeper causes of economic strain. Initiatives such as Help to Buy have been criticised for inflating prices rather than making homes more affordable.

Lasting change will require structural reform. Linking the minimum wage to regional living costs would help align pay with reality rather than a national average. Expanding apprenticeships and vocational training would open alternative routes to stable, well paid employment. Increasing the supply of affordable housing and introducing fair rent caps could allow young people to save and plan rather than spend most of their income on rent.

There are successful models abroad. Germany’s apprenticeship system provides clear routes to skilled, secure work. In the Netherlands, social housing ensures that rent remains within reach for ordinary workers. The United Kingdom could learn from such approaches to rebuild fairness and opportunity.

Britain’s Future Depends on Its Youth

The cost of living crisis is more than a moment of economic pressure. It is a challenge to the country’s long term stability. If young people cannot build secure, independent lives, the effects will ripple far beyond individual hardship. Innovation, productivity and social cohesion all depend on a generation that feels invested in the future.

Rebuilding that confidence requires more than short term fixes. It demands policies that restore the link between work and opportunity. The real question is not whether young people can survive the cost of living crisis, but whether Britain can thrive without their success.

For now, many young people are not chasing dreams of wealth, only the hope of stability and even that seems to be slipping away.