“Being born a woman is my awful tragedy.” Sylvia Plath journalled in 1959, four years before her death. “From the moment I was conceived I was doomed to sprout breasts and a womb and to adore men who are the enemies of my kind.”

A year later, in 1960, poet Anne Sexton underwent an illegal abortion — an act that was seen as wicked and unthinkable, but that would later become the groundwork for one of her most haunting and prophetic poems.

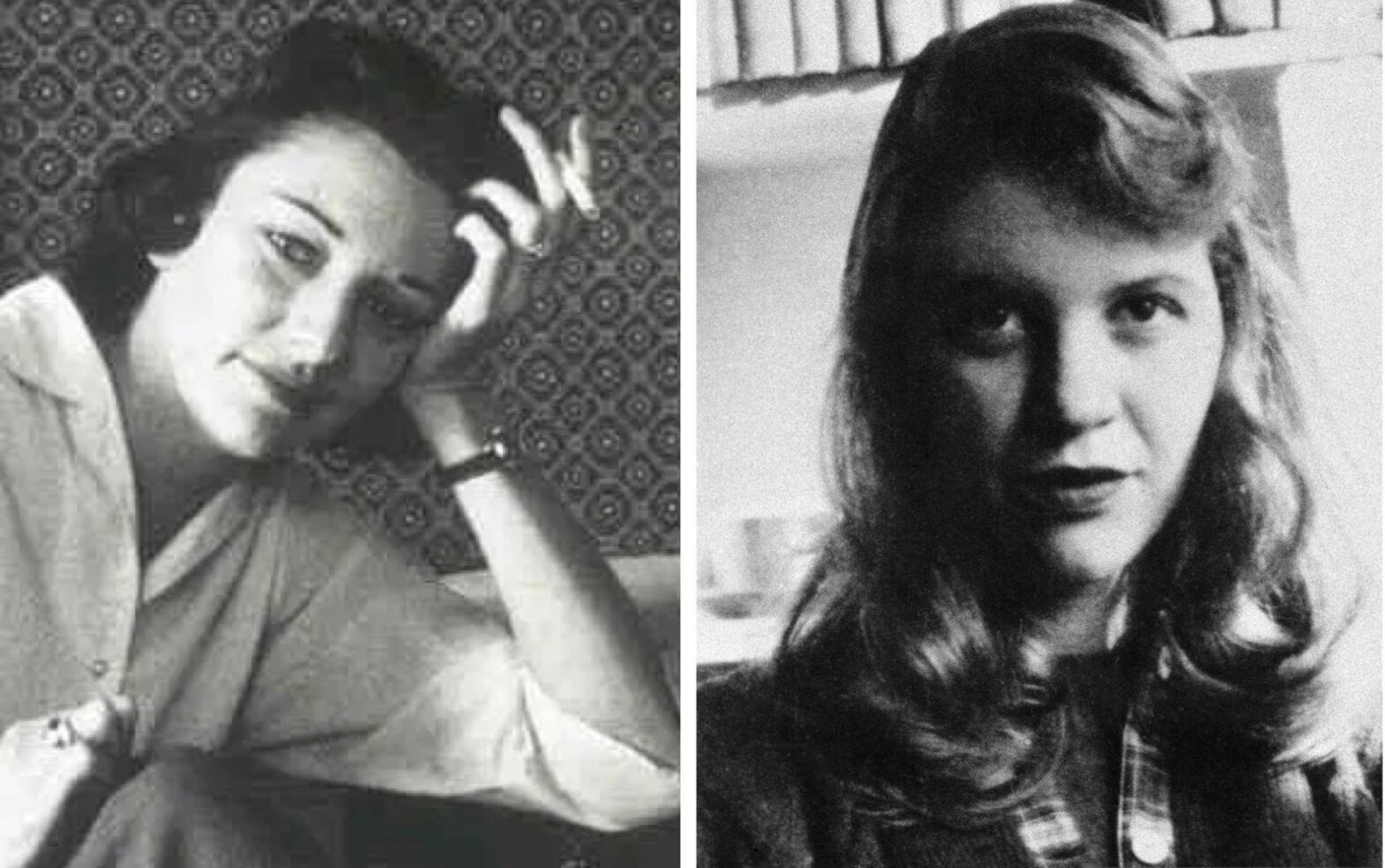

Two voices fundamental to the feminist movement, both Plath and Sexton produced some of the most important confessional poetry of the twentieth century. Fearless in their raw depictions of the struggles faced by so many, even in death they continue to vouch for the rights of women today. Their work is intergenerational in its ability to highlight the struggles of womanhood, stretching across time to unite us in resistance as we face the unfathomable political decisions that are being made for us.

So, how do the works of both Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton still retain such power as they span beyond their lifetimes? How do these two voices, forged in staggering grief and feminine fury, offer us so much reassurance in a time of such pervasive uncertainty?

More than nine months into Donald Trump’s second term as President of the United States, it is perhaps more apparent now than ever that women’s rights in the U.S aren’t simply being neglected, they are being undone. No matter the distance between us, the revocation of women’s freedom in America resonates globally, touching all of us in an ongoing and shared gender struggle. This revocation of rights is not simply an impending possibility, but a terrifyingly rapid reality that affects women everywhere.

The victory of Roe v. Wade in 1973 was revolutionary in its nationwide guarantee of the right to choose. That was until three years later, when The Hyde Amendment of 1976 saw low-income women banned from using government funded health plans and resources to aid safe abortion. This decision segregated groups of women according to financial means and social status, and what followed was a barbaric domino effect — state after state implicated hundreds of restrictions, only calling for exceptions in very limited cases, such as rape, incest, or endangerment to the mother’s life. So, while this amendment didn’t completely ban abortion, it just made it economically inaccessible for millions.

This is when we are able to turn to Anne Sexton, who lived the reality of an illegal termination in 1960 and penned her poem The Abortion two years later. The piece encapsulates the unbearable guilt and secrecy that surrounds the act, and the inner turmoil that follows. Living in Massachusetts at the time, where abortion was strictly illegal (unless the pregnancy posed risk to the woman’s life), Sexton jeopardized herself in so many ways — legally, socially, and emotionally. Her decision to expose herself in this way mirrors the same dire consequences that many women face under today’s abortion laws, but exudes the courage and reassurance that feels crucial to surviving them.

Amidst her fascinating ability to lend a voice to both sides of her inner turmoil, not once does Sexton argue for or against, nor are her unbiased words shrouded in some political smokescreen. Instead, while reassuring us that she has been there too, Sexton inadvertently reminds us that women have endured this kind of fear before, and that change has followed. There is something deeply comforting and powerful in her words; a woman long passed, with many experiences and ideas so different to our own, eternally reassuring us that transformation is possible. Her forthright tone refuses sentiment or sympathy, and The Abortion reinstates the profound complexity of the decision, as well as the inevitable tsunami of emotions that men—especially those who weaponise the issue for political gain—will never understand.

Earlier this year, Trump declared that it “took courage” to overturn Roe v. Wade, an egotistical stance that transforms the distruction of women’s rights into nothing more than a moment of self-regard. To the President, “pro-life” appears to be less of a political conviction, and more of a contrived, populist scrabble for recognition. It is not a moral stance, but a performance; a hollow slogan that guarantees applause at rallies and headlines in the news. But abortion is not a cheer-or-boo moment — it is not a tagline, nor a decoration, and being “pro-life” is not as simple as shutting down abortion clinics to declare moral one-upmanship. Declaring oneself as being anti-abortion is so easy for those who stand so far from the consequences, flattening women’s trauma into slogans for badges, for bumper stickers, for decals on the sides of guns. From six feet under, Plath and Sexton do the opposite. Screaming through the soil, their writing spills from the pages and encapsulates the total mind-fuck of it all; the guilt, the relief, the crippling fear, while navigating the instinctive pull toward motherhood — a complexity no political watchword could ever trivialise.

For so many women today, survival boils down to making oneself small and unassuming, and for those existing under Trump-era abortion laws, passivity and compliance become crucial strategies to avoid criminal liability. In her 1961 poem Tulips, Plath transforms this enforced stillness into something empowering: a subtle, hard-won assertion of agency over one’s own body. With her body and mind at first reduced to passivity under the guise of male doctors, Plath’s speaker gradually finds power in reclaiming control over her choices of what to feel, what to notice, and how to respond. While the poem never explicitly mentions abortion, its depiction of a woman constantly being observed and constrained by “the eyes of the world” echoes the scrutiny that many still face today. Plath doesn’t shy away from directly addressing the systems governed by male authority, and by subverting traditional femininity and adopting the façade of surface level gentility, she turns societal expectations into the only tool she needs to rebel. Through her silent yet unyielding reclamation of self-control, Plath offers a steady hand to those scrabbling to find their footing in a world that, in recent years, has seemed unrelentingly hostile towards women. Tulips is another reminder that, when faced with unimaginably challenging circumstances and riddled with anxiety over the what-ifs, we can look introspectively for ways to regain authority over what the world thinks we should do with our bodies.

While I recognise that reading feminist poetry alone will not guarantee laws be rewritten, nor is it an answer to every issue surrounding inequality, I do believe in one thing for certain: Through the works of writers like Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, we are reminded of the benefits of shared experiences and belief — whether that be in ourselves, in the possibility of change, or in the small acts we can do to build the larger picture of choice. In a world so unapologetic in its cruelness, and unforgiving in its control, we are reassured by both poets that there is still unimaginable strength in persistence. No law, no bigot, and no regimented system of control can strip us of the invaluable power found in the experiences of those who came before us.

Plath and Sexton remind us that amidst the chaos of rewritten policies, stripped back rights, and the abuse of power in the name of egocentricity, the one thing that can never be quietened is the echo of our voices. Anne Sexton once wrote the words, “I am torn in two, but I will conquer myself.” a mantra that reminds us of the importance of addressing our fears and doubts in order to regain control.