The superficiality when you may hear, “Can I have a chai tea matcha latcha latte,” is almost as superfluous as the exaggeration sounds. Of course, this is a hyperbolic extension of the real issue; one culture idealised and “Westernised” to become nothing more than a simplified idea with a complete loss of meaning (at least it might be tasty?). Perhaps this is what we might think of as marginalised communities — in my case, as an Asian Indian woman and the use of our language. Chai actually means tea, so in the case of this completely imaginary person, what they actually mean is, “Can I have a tea tea matcha latte (milky green tea esque coffee).” It sounds as horrendous as it actually sounds.

What you may be thinking is: why, if anything, do these issues matter? It all boils down to a largely imperative (pun intended) and large part of history: colonialism. It seems that once the British Empire tasted a morsel of gold mines, enslaved labour and generated generational wealth, the idea of greed almost became similar to a love of crack. Now more than ever, even in a world with the greatest lengths of technology, the understanding of identity or even learning comes with a limited price; that being appreciation and acknowledgement for things that are not ours in the first place.

Even the word ours denotes a funny feeling of belonging. What actually is ours in the UK? Could it be the magical flags appearing on roundabouts? Is it the air we breathe that is conditioned to be condensed condescending condensation of being “English”? It creates an icky feeling for some. But I shall include a small, albeit short, history lesson (insert learned knowledge as a prior History teacher for 10 years — yes, I’m still questioned on factual events).

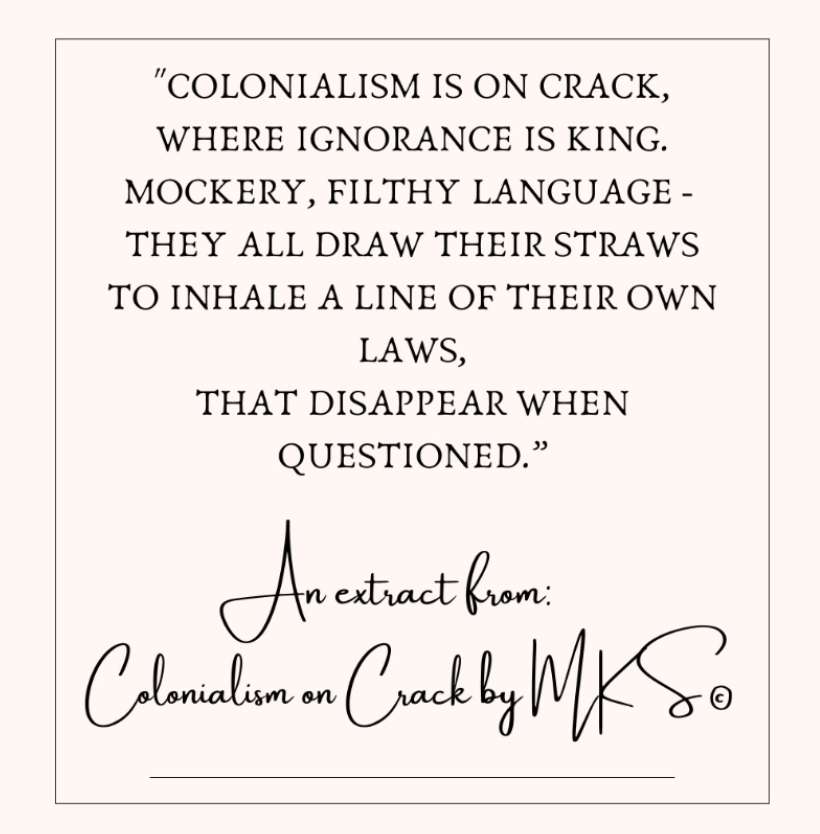

The British Empire is currently taught in the curriculum to provide a balanced understanding of what we “gained” and the horrific treatment and loss of those we essentially stole from. You can’t rebrand slavery as something wholesome; it wasn’t. The reason you meditate, the yoga you practise for example; most things you sensorially experience may not actually originate in the UK. I’ve always said this: privilege is like a colonial conquest — you pick and choose the things you like and destroy the rest without accountability. Sometimes it’s better to illustrate the gravity of colonialism with creative words. Here is an extract from my poem, Colonialism on Crack, to help envision this idea:

The poem began as a raw reaction to how colonial voices still sound in everyday speech, fashion, and food. It’s laced with irony and exhaustion; the kind that comes from watching your culture re branded and resold. The title, Colonialism on Crack, isn’t about shock value; it’s about addiction. Addiction to ownership, to the glamorisation of ownership and to the illusion that “borrowing” beauty is the same as belonging.

For contextual basis, my heritage lies with Sikh Punjabi roots in Amritsar. My great-grandmother met Gandhi in her village; so history’s thread is still wound into my blood that was not that long ago. The British Raj in India (1858–1947) operated on economic extraction, be it Indian textiles, jewels, spices, and tea, with cultural elements such as henna being “adopted” as fun moments of narrow gratification without meaning. To further this idea, it is well documented that many Asian Bollywood actresses were chosen because of their “fair” or “light” skin colour; it was seen as an issue to be dark-skinned, a Western ideal that has existed for hundreds of years.

The anglicisation of culture became important to continue with language; English education was often enforced in colonies at the expense of local dialects. “Elite” Indians were taught to mock and ridicule their own expressions of language, which now harks back to the simple phrase of “chai latte” being an example in today’s society that seems outdated and embarrassing.

Cultural and racial hierarchies portrayed colonised communities as “exotic” (I have been described with this term when I dated before marriage), “other,” and inferior, now embedded into the ever-growing and repetitive rhetoric of the far-right in the political space. Many marginalised communities internalised these “enforced stereotypes” and unfortunately look at our cultures as consumable (like crack) rather than a richness of beautiful communities.

Let’s take Prada’s recent Spring/Summer 2026 collection featuring open-toe leather sandals that almost looked identical to the traditional Indian Kolhapuri chappal from Maharashtra. The design was simply marketed as “a leather sandal” with no mention of India or its centuries-old tradition of craftsmanship. Backlash from Indian communities and the industry prompted criticism describing this fashion as “new-age colonialism under the garb of fashion.” Did Prada apologise or acknowledge it? No — which is expected.

All I can say is that if you are going to “borrow” ideas: don’t hate us because you ain’t us. And maybe as designs and craftsmanship are so good, it feels like crack to wear and model them again and again as some “spanking new idea” when it’s not. When the UK was building wattle-and-daub houses, India was building marble palaces.

This, however, does not mean that every Western business or brand should be demonised under one stereotype of being “bad” and division is not what we want to create more of. No. There are plenty of examples where the multicultural richness and diversity of the UK are celebrated by so many who want to learn and grow their understanding of the world. Yes, learning, which is very exciting for an ex-teacher.

There is no real protocol except acknowledgement and appreciation that inspires others. Notable examples recently include nationwide and international celebrations of Diwali. Swiss International Airlines created the “Home is where your people are” campaign, aimed at the South Asian diaspora and focusing on the connection of loved ones rather than the location of one’s home. The question remains of how deeply companies engage with culture rather than surface-level marketing. For example, it’s very nice to bake a Diwali-inspired cake — but do the origins rather than the visuals emote appreciation or tokenism?

Genuine appreciation is about partnership and understanding. When a brand works withcommunities for example, hiring South Asian creatives, collaborating with local artisans, or giving back to the people who inspire their designs, it moves to integrity, disregarding imitation. Tokenism asks, “What will look good?”; appreciation asks, “Who should we honour?”

Let’s take jewellery. It’s a token of appreciation for beauty and shiny things; some pieces are sentimental, and some are valued because of the brand itself. However, the recognition of one’s own heritage alongside a wider sense of community connection, also lies with marginalised creators and their personal brands that are supported and celebrated.

Rani & Co. are personally one of my favourites; intricate designs with necklaces and bracelets that celebrate Hindu female deities, Greek goddesses (among other beautiful symbols), embodying the divine feminine and bold energy for all women and wearers of the designs. It feels meaningful to see a jewellery brand using Indian heritage and design, created by someone who shares similar experiences with our backgrounds. Culture can be celebrated rather than commodified.

Ramona Gohil, the owner of Rani & Co., states the following:

“Every time we host an event, I’m blown away by the familiar faces who show up just to celebrate with us. … It never feels like a ‘customer event’ — it feels like hanging out with friends. And that’s what makes it so special.”

— Romona Gohil, founder of Rani & Co.

A better question to ask is this: what would cultural appreciation actually look like? Sometimes it begins with learning the pronunciation of someone’s name — because it is their identity. My first name is Mara; I have been called many other names under the sun (e.g. Margot, Maria), but it’s quite simple to do!

Colonialism might have changed its clothes; trading uniforms for runways and propaganda for PR. True decolonisation, in my view, means partnership and collaboration, not isolation. It means who made what you wear, knowing who taught you, and the words you might randomly quote for Instagram inspo. It means turning “chai tea” back into what it always was: just chai. And just enough.

I have always said that poetry is my cue card for emotion; for me, writing is a way to purge from that inherited ache. It is a way to reclaim what history made heavy and to make it my own again. My poem started as anger because British history has caused severe destruction and consequences, affecting countless communities in the past, today, and for generations to come. Perhaps now the words feel like a prayer. Colonialism on crack is not just history repeating; it’s history remixing itself badly.

Maybe one day we’ll stop overdosing on other people’s beauty, identity and cultures, finally learning how to appreciate them. Everyone carries a story; to honour one’s tale keeps culture alive. Because maybe, decolonising isn’t about rewriting history: it’s about remembering who wrote it first.