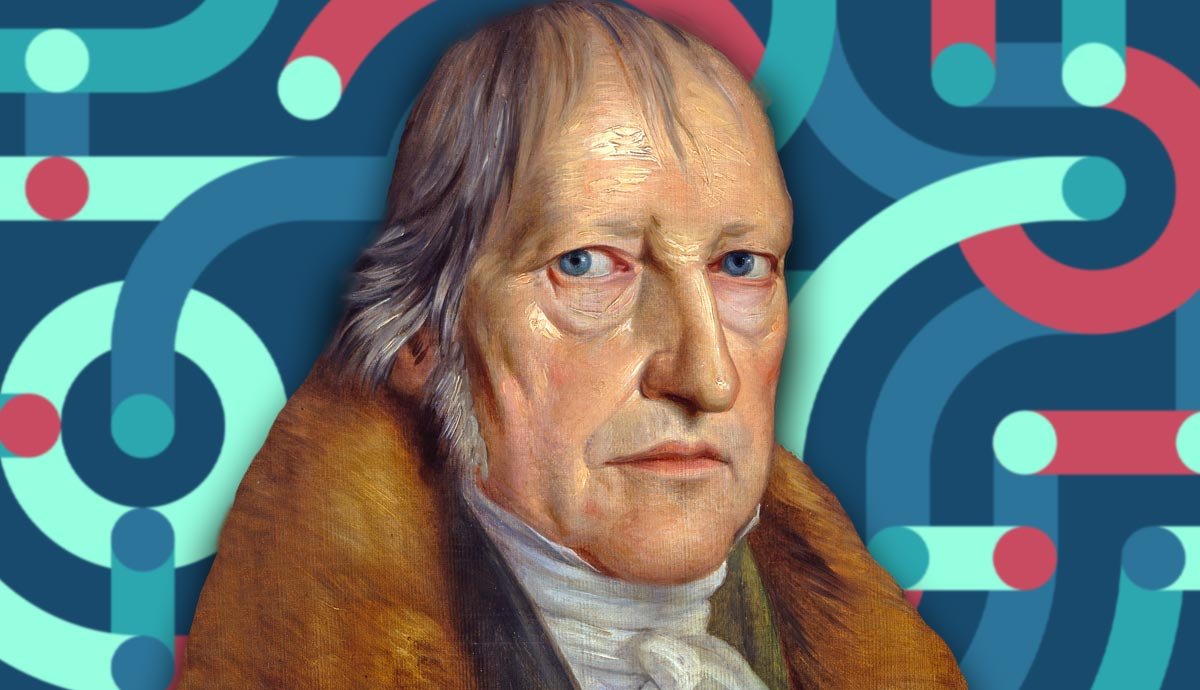

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) was a German philosopher during the late 18thand early 19th centuries and was key in the development of German idealism. Hegel’s work varies from idealism to the concept of the “Geist”, the philosophy of art, and metaphysics. Therefore, Hegel is not easy to read nor is he easy to interpret or apply to politics.

Consequently, for the purpose of this article we need to focus on one of Hegel’s key concepts. This article will concentrate on Hegel’s idea of – dialectics. Dialectics can be defined as ‘Hegel’s method for arguing against the earlier, less sophisticated definitions or views and for the more sophisticated ones later.’

Simply, Hegel’s dialectical method is the process by which an idea is challenged over time in order to produce a higher more well-developed version of the idea later. This process is often described as the initial hypothesis (idea), which is challenged by an antithesis (contrary idea), both are eventually incorporated into the synthesis (sophisticated idea).

Subsequently, Hegel’s dialectical method is a means by which we as humans have developed overtime by; proposing ideas, which are then challenged, leading to a compromise and ultimately progress. Belief in this method is also known as dialectical idealism – the concept that human history has developed through the dialectical approach towards ideas.

However, this article asks the question can Hegel’s dialectical method be applied to the development and history of Marxism in Europe? This article focuses on Europe so as to maintain a line of argument that does not descend into obscurity, due to the complexity of the ideas discussed. In order to comprehensively answer this question we should first discuss the relationship between Hegel and Marx.

Hegel and Marx – Teacher and Student

Despite never actually seeing Hegel’s lectures in person, Marx became interested in Hegel’s ideas after his death in the 1830s. Marx joined the Doctors Club where Hegel’s ideas were discussed among the radical thinkers of the student body. Marx then joined the Young Hegelians in 1837. This was significant as it introduced him to the dialectical method, which was highly endorsed by the group.

Marx took Hegel’s dialectical method and adapted it for his pre-conceived ideas of class. The result – dialectical materialism. Marx’s dialectical materialism can be defined as the view of ‘history not as the self-realisation of ideas, but as driven by material and socio-economic factors…’ Marx adapted Hegel’s dialectics to be applied towards material difference and the economy rather than the gradual development of ideas.

Given this link between Marx’s ideas and Hegel’s, this article believes that Hegel’s dialectics can be used to interpret the historical development of Marxist thought in Europe. Ultimately,leading to the modern forms of Marxist thought that still exist to a less or greater extent today.

Applying dialectics to Marxist history

Albeit a simplification, for the sake of this article let us interpret Hegel’s dialectics as the progressive shift from hypothesis – antithesis – synthesis. This will provide a succinct structure to the following analysis of Marxist history and ideas in the European context. In order to fully address the development of Marxist history the following hypothesis, will discuss Marx’s work as a collective whole rather than individual works.

Hypothesis

A crass summary of Marx’s work would suggest that under the capitalist system the proletariat become class conscious as a result of the commodification, estrangement, and alienation of labour. Marx’s remedy, being a revolutionary overthrow of capitalism and establishment of a ‘…dictatorship of the proletariat…’

Marx presents aspects of this argument pre-The Communist Manifesto in his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1844) – ‘…the whole society must fall apart into the two classes – the property-owners and the propertyless workers.’ Marx believed that society would divide along lines of class due to the effects of dialectical materialism.

Marx’s overall hypothesis is to suggest that to counter capitalism the working-class must become conscious of their status and their exploitation – ‘[political economy] produces intelligence [for the bourgeoisie] – but for the worker idiocy, cretinism.’ This idea and Marx’s proscription of revolution can be used as a summarised hypothesis, in this dialectical analysis of his ideas.

Antithesis

This article would argue that the most comprehensive antithesis to Marx’s ideas are not political, rather economical. The Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1913) this article citesas the economic antithesis of Marxist ideas in the later 19th century due to the seismic growth in free-market economies and globalization that occurred during this period.

One characteristic of this period was the growth of railroads in the U.S., United Kingdom, and other European nations. Development in ‘rust-resistant steel became less expensive, …able to support heavier locomotives pulling heavier loads.’ The growth of the railroads had knock-on effects for stock exchanges.

Richard S. Grossman noted, ‘foreign railroads constituted some of the largest companies traded on the British exchanges.’ Subsequently, the technological advancement that fuelled the Second Industrial Revolution, improving the interconnectedness of national economies, is arguably the truest antithesis to Marx’s ideas.

During the same time period in which Marx’s ideas were becoming more widespread (First International 1864, Second International 1889), capitalist markets were experiencing a period of economic “boom”. Adam Tooze and Ted Fertik believe – ‘What underpinned the mounting level of trade integration before 1914 was… [the] supply side shock delivered by falling transport costs.’

Therefore, the antithesis to Marx’s political ideas in the 19th century was the expansion of capitalist economies as a result of declining transport costs during the Second Industrial Revolution.

Synthesis

This article believes that the synthesis of Marx’s ideas and the Second Industrial Revolution in Europe can be found in the growth of both democratic socialist and social-democratic parties during the 20th century.

A factor that contributed to the growth of socialist parties in Europe as a result of both Marxist thought and capitalism are trade unions. Trade unions became intertwined with political parties across Europe and were fundamental to broadening their support base.

In Britain trade unionists (‘1905, 1,997,000 people’) were integral to the growth of the Labour party as union dues subsidised their candidates in parliament in order to represent their interests.

Subsequently, in reaction to both the development of Marx’s ideas and the economic growth of the later 19th century, trade unions grew in membership to represent the interest of the working-class in parliaments and consequently, the growth of the Labour party in Britain.

Trade unions were not the only consequence of the synthesis between Marxism and capitalism in Europe, as displayed in the development of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), founded in 1875.

As the origins of the SDP are founded in the combination of a Marxist group and a group more closely aligned with the traditional government – ‘the state socialist Lassalleans… and the Marxist-oriented Eisenachers.’ The subsequent success of this integration between the parliamentary socialists and the Marxists to form the SDP can be seen in the fact the party received ‘over 2 million votes by 1898.’

As successful the synthesis was in the form of the Labour party in Britain and the SDP in Germany, perhaps the most profound result of the synthesis can be found in Sweden’s Social Democratic Party. Richard F. Tomasson argued the party represented ‘the most successful social democratic movement in Western Europe.’ Evidence of the Social Democrats success in Sweden can be seen in their impact on unemployment in the 1930s – ‘from 139,000 in July 1933, to 21,000 in August 1936, and to 9,360 in August 1937.’

The Social Democrats success in fusing both Marxist/ Socialist traditions with pragmatic economic management can be seen in the comments from economist Carl Landauer who wrote – ‘The history of socialism knows no more successful combination of pragmatism… [and] loyalty to the socialist tradition… than the policies of the Swedish Social Democrats during the 1930s.’

Conclusion

This article has made the argument that Hegel’s work on dialectics can be applied to the history of Marxist thought in Europe and has analysed the resulting; hypothesis – antithesis – synthesis, this process has produced.

Furthermore, this article has argued that the antithesis to Marxist thought in the late 19th was not necessarily one based on a political idea. Rather this article believes it was the rapid economic growth towards the end of the century that provides the most adequate counterpart to Marx’s ideas and clearest form of challenge in the form of capitalist expansion.

It can also be concluded that Marx’s initial hypothesis is an example of dialectical idealism whereas the antithesis belongs to dialectical materialism, further strengthening the link between Hegel’s work and Marx’s.

Subsequently, this article has found that the synthesis of Marx’s thought (particularly on the commodification and the alienation of labour) with capitalist economic growth is the resultant expansion in the number of democratic socialist and social democratic parliamentary parties in Europe.

In Britian this was displayed in the growth of the trade union movement which sought to provide a voice to the working-class by sponsoring Labour party members of parliament, in order to campaign for their interests. The impact of this can be seen in the increasing amountof Labour MPs in parliament between 1900-1910 from two to forty MPs (prior to the introduction of MP salaries in 1911).

In Germany the rapid expansion of the SDP was based on the fusion of traditional political interests and Marxist ideas, effectively personifying the very process this article has sought argued. The impressive electoral results of the SDP in the 1890s further displays the political popularity of this combination of traditional political mechanisms with the pragmatic implementation of Marxist thought.

Lastly in Sweden, the success of the Social Democrats can be seen in its rich history of economic pragmatism, socialist idealism, and welfarism. The result being staggering electoral success, between 1918-2018; of the 35 opportunities to be in government the Social Democrats have formed 25 governments over that 100-year period. A success that would hasonly been achievable through the party’s effective use of economic pragmatism whilst maintaining socialist values.

Overall, this article believes that Hegel’s dialectics are a useful method for re-interpreting the development of Marxist ideas in Europe and the history of them. Hegel’s framework allows us to draw conclusions from the challenging process between hypothesis and antithesis – Marxism and Capitalism. The result of this process, having a seismic impact on the development of democratic socialist and social democrat parties in Europe during the 20thcentury.