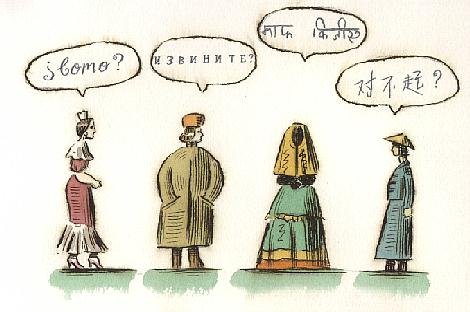

In a city just south of Seoul, the government is ordering cafés to erase English from their signs. In France, Le Académie Française continues to issue new warnings against the use of Franglais. Meanwhile, in the U.K., the Oxford English Dictionary adds over fifty Korean and Japanese words to its pages. And Spanish Royalty decrees that English words should also be added to its dictionary. These little linguistic snapshots, scattered across the last decade, establish a veiled portrait of who the world listens to.

For centuries, linguistic borrowing moved in one direction. English, carried by the empire, Hollywood, and Silicon Valley has defined modernity. To speak it fluently was to belong to the future. Now the current flows in several directions at once. Korea sells its pop-cultural lexicon; France defends its linguistic soul; and English, still a conqueror, serves as a vessel for globalisation’s mixed offspring. Each borrowed word reflects a quiet transfer of power.

Language has never been about what is proper. It has always been part of the tools used in political power: a mirror of who controls power and how they wield it.

As a currency of influence, language has long been traded, borrowed, and imposed. When English spread across the globe, it carried not just grammar but both economic and military power. First it was the language of conquest, then of commerce and lastly culture and science. The world remains wrapped in its whirlpool.

For two centuries this dominance went largely unchallenged. From the White House to the BBC World Service, English defined what knowledge and ethos sounded like. Brain drain was always headed to the U.S. and U.K universities; professors looking for refuge and protection for their research had an open door. While other languages like French managed to retain its importance in diplomatic circles and Spanish was able to carve out a bigger space due to the sheer number of native speakers; English always had soft and hard power fused to it. Until recently, English remained the language of academia, advertising, and aspiration. To borrow an English word was to borrow prestige: the French have a word for the weekend, but it still sounds cooler to say “le weekend”.

Such borrowing, however, is shifting. As the cultural axis tilts eastward, so do linguistic patterns. The headwaters once in London and New York now seem to flow back their previous delta in Seoul, Tokyo, and Shanghai. English speakers type unni or kawaii without translation, their feeds scattered with words from cultures once deemed “other.”

These borrowings are not passive. They are soft power in motion: the subtle conquest by culture. Yet English has always been a linguistic sponge, and that may be its shield. Historically English has always been an amalgamation, a melting pot, for other languages. It has “beef“ and “advice“ from French, “skill“ and “husband“ from Old Norse, “cheese“ and “butter“ from Latin. So now when a teenager says they want to eat ramen or tanghulu, while they are not thinking of politics, their speech quietly traces global influence. Linguistic borrowing is both aesthetic and strategic where adding words either by royal decrees or not to the dictionary becomes a political statement, charting where empires fade and new ones emerge.

Take Paris as an example, with the Académie Française once again declaring war on Franglais. The Académie was founded in 1635 but now it is confronting a new invader: digital slang. Its latest warning condemns an invasive anglicisation of public life, where drive piétons (pickup zones) and bleisure (business plus leisure) creep into daily speech. Especially in technology, “Californisms” as they are called like “follower”, “hashtag”, and “start-up” are seen as linguistic trespassers. The Académie’s fear is less grammatical than existential. It warns that casual English creates “linguistic insecurity,” dividing elites who understand it from citizens who do not. The struggle for purity mirrors France’s struggle to define itself in a world where influence now speaks in borrowed tongues.

In Korea, that anxiety takes a different shape. Officials there pay shop owners to replace English signboards with Hangul, the Korean alphabet. On paper it is city planning; symbolically, it is reclamation. One official described the goal as “sharing the beauty of Hangul.” Once a marker of modernity, English now looks out of place on the streets of a nation exporting its own vocabulary. The reversal is striking. South Korea, once obsessed with English proficiency as a path to social mobility, now polices its imports while celebrating its exports. Researchers at the National Institute of Korean Language work tirelessly to invent Hangul alternatives to “deepfake” and “influencer”, a task they call “pouring water into a bottomless pot.” Yet the effort continues, animated by the belief that language is not only communication but identity.

To understand that France and Korea both fight to reclaim their languages while English survives by absorption is to see how a lingua franca digests foreign words with the confidence of an empire not afraid of dilution. The Oxford English Dictionary, most known for being the authority on the English language, has become a cultural seismograph, recording the tremors and waves of shifting influence.

This year, it added twenty-six Korean terms, among them bulgogi, manhwa, hallyu, and mukbang. The editors described the move as “riding the crest of the Korean wave,” a quiet acknowledgment that soft power once radiating from the West now begins to glow from Seoul. Last year already there had been another expansion: twenty-three Japanese words, from katsu and donburi to kintsugi and isekai. Each addition was treated not as exotic but as part of everyday life.

English’s reach has always depended on this elasticity. It conquers through inclusion, it endures by transforming foreign words into its own heritage. Yet these dictionary updates have never been neutral. They are geopolitical checks, tracing who commands attention in the global stage. When omotenashi and oppa share a page with selfie and Brexit, the dictionary is not grammar but a map of power.

If English is porous by design, Spanish has learned to be adaptable by necessity. In December 2024, Spain’s Royal Academy (RAE) added spoiler, developer, funk, and groupie not to corrupt, but as realism. Unlike the linguistic purism of the French and Korean, the RAE framed the update as reflecting how Spanish speakers actually live, work, and consume culture. Words from technology, gastronomy, and music entered through coexistence.

The Spanish pragmatism signals a quiet philosophical shift, from protectionism toward hybridity. In a world where digital life erases borders, purity feels anachronistic. Inclusions reflect humility: the recognition that no language, however vast, can afford to stand still.

Survival now in global communication may demand not dominance, but accessibility. If English built the twentieth century, Mandarin may be writing the twenty-first. From Nairobi to Riyadh, classrooms now echo with tones once confined to the East. In Kenya, pupils sing the Chinese anthem before lessons; in Saudi Arabia, Mandarin is mandatory in secondary schools. Across the Middle East and Africa, the spread of Chinese programs, which are often supported by Confucius Institutes, shows soft power at work. Conquering through culture.

Unlike imperial languages of the past, Mandarin spreads differently, focusing on young minds. For young Africans, Arabs, and Pacific Islanders, it promises mobility and access to a changing economic order. To learn it, is to align with the world’s next centre of gravity just as learning English a century ago meant. The rivalry between English and Mandarin is just another battle between the fight for political hegemonic power. It is now clear that the contest between an aging lingua franca and an ascendant one is escalating at a rapid pace in this decade. Hence why for English every borrowed word carries a weight, and leveraging its own dictionary and historical absorption pattern is essential to its survival. A generation ago, we borrowed from Hollywood. Tomorrow, maybe from Shanghai. The question is not whose words we use, but how quickly it may change during this century.