“The whole purpose of education is to turn mirrors into windows”

American journalist Sydney J Harris’ quote could perhaps shed some light upon the harsh truth of university education in 2025: that its “purpose” is becoming diluted.

In the Summer of 2025, UCAS figures reported an all-time high in the university and college acceptance rate for 18 year olds in the UK, reaching around 75%.

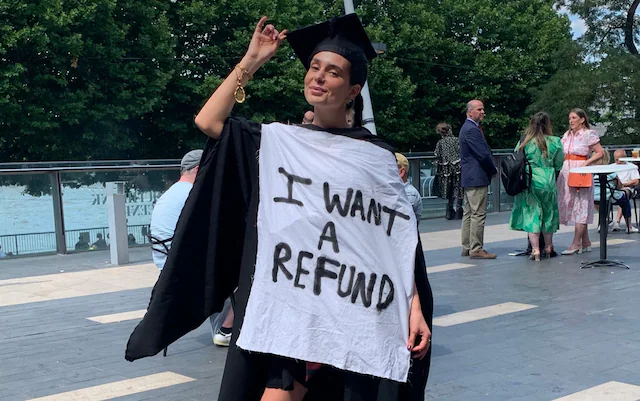

However, just half of First-class University graduates from 2021/22 were in full-time employment, with 6% remaining unemployed. With this knowledge alone, there is little certainty that university ‘turns mirrors into windows’ . The assumption that every degree will simply birth job opportunities is possibly misleading for many graduates.

The Key Issue

Finding a definitive cause of this lost purpose within universities nationwide is near impossible. Perhaps it is the endless number of unnecessary degree options, or those young adults who simply seek the freedom of the “university experience”?

While these factors undoubtedly contribute, they may be obscuring the key issue of inadequate careers guidance being offered to young adults. For many young people, university presents itself as the most logical form of educational progression; these students have just acquired level 3 qualifications, with an undergraduate degree offering the “next level” in this academic model. While this provides a secure, perhaps even risk-averse pathway for students, this model neglects those whose skills and potential lie elsewhere.

Instead of guiding each and every student towards a university career pathway, other pathways should be equally considered. Encouraging apprenticeship programs, internships, or even short-term work experience is shown to significantly improve employment prospects for young people.

A strong example of this can be found in Germany, where a “dual education” (Duales Ausbildungssystem) system is in operation. A September 2025 survey found that Germany’s youth unemployment figures were indeed half that of the UK, at just 6.5%. This has largely been found to have been rooted in their nationwide push for more vocational and prestigious apprenticeship opportunities than most developed European countries. Through offering (paid) dual education courses in over 300 different professions, early career paths have consequently become both more practical and beneficial for the average student to access a wealth of employment opportunities. Such success only fuels the notion that a restructuring of the UK education system would be the best approach in order to tackle dismal national youth unemployment.

What can be done?

Ultimately, the best way for post-18 education to be realistically restructured in the long term is unclear. However, spreading awareness of alternative options to university would be far from unnecessary. By allowing students to be more informed with regards to their career options, there are much greater odds of low employability degrees being filled every year, particularly by students who see these courses as their only post-18 option.

Alongside this, removing the potential social stigmas around vocational and apprentice-style training could prove fruitful in beginning to reshape society’s outlook. Many high-attaining students often see choosing these career paths as not fulfilling their academic potential in comparison to obtaining a well-respected university degree.

However, the potential for an expansion of degree apprenticeship programs highlights how similar academic achievement could be reached through dual education. The slow expansion of these programs points to our governments, who should be held more accountable for failing to properly invest in these, instead of subsidising low employability and low financial yield university courses. Recent financial data proves this, as 1 in 2 graduates in the 2024/25 cohort are projected to never fully repay their student debts, highlighting just how necessary investment into alternative education is, particularly amidst a government troubled with piling economic issues.

In theory, the idea of education “turning mirrors into windows” is not a sweeping statement fit for all university students. Education in other forms, such as apprenticeships, has the potential however to guide those perhaps misinformed students who choose the safety of university life over a more practical career pathway for their skillset.