In a society dominated by algorithmic systems, modern audiences encounter content shaped by automated aesthetics. While this is widely acknowledged, what matters is understanding the historical continuity behind this mechanism. There is a clear line connecting ideology, image, and algorithm — a causal chain that brings us into the condition of contemporary modernity.

In Immortality, Kundera reflects on the transition from an ideology-based society to an image-based one. His example is Marxism, which emerged as a powerful ideological movement in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century Europe. Early Marxists gathered in small circles to study the manifesto; as the rhetoric travelled outward, its ideas had to be simplified to enter new social environments. These new circles reproduced the same dynamic, diluting the message further each time.

When Marxism reached the height of its political power, it had already been reduced to a small cluster of slogans — often so incoherent that they barely resembled a systematic ideology. Soviet history shows this vividly. What remained of Marx was no longer a logical structure of thought but a repertoire of images and emblems: the smiling worker with a hammer, or the White comrade extending a hand to Asian or Black workers. For Kundera, this is emblematic of a broader, global process: the conversion of ideology into imagology.

Kundera illustrates a contemporary form of imagology through the example of gym entrepreneurship. Aware of how clients perceive reality, gym owners began installing mirrors everywhere—so extensively that one cannot escape their own reflection. These mirrors are not meant for monitoring technique, but for encouraging clients to see themselves as people who take care of their bodies, health, and overall wellbeing. This reflected image becomes a kind of self-affirmation, positioning individuals within a particular social hierarchy. The gym mirror does not merely show the body; it produces an image that confers belonging, identity, and a sense of personal value. The same mechanisms occur across industries – fashion, politics, TV, aesthetic preferences and so on.

Imagology is not a new phenomenon, but its victory over ideology is decisive. And in a similar movement, imagology became victorious over reality itself. Reality, for most of history, remained graspable. A peasant, for example, understood his immediate surroundings: how to bake bread, build shelter, or interpret the views of the village priest and schoolteacher. Reality could not be falsified — no one could claim that agriculture was flourishing if food was scarce.

Globalisation, technological complexity, and mass media weakened this grip on the real. Our environments became opaque, increasingly mediated by systems few understand. As representations multiplied and life became abstracted, people grew less invested in the empirical world. Even when reality could be partially apprehended, it was less attractive than its mediated counterpart.

Reality became something we perceived through instruction — through what we were told to think, rather than what we saw or felt. As reality drifted from lived experience, individuals had to construct their sense of it. Media content, public opinion, and received narratives became the materials out of which reality was assembled. Public opinion polls rose to the status of a higher, democratic truth — the central instrument of imagology’s power and a mechanism that kept imagology in harmony with society.

Because societies are fractured and plural, these polls generate multiple simultaneous truths, each within its own subgroup. In a fragmented social landscape, localised “public opinions” function as versions of reality. Imagology never conflicts with these truths because it is built from them; it can only affirm them, and thus it always appears correct. Kundera writes that all human systems eventually end — yet he also suggests that imagining a successor to this mechanism is almost impossible.

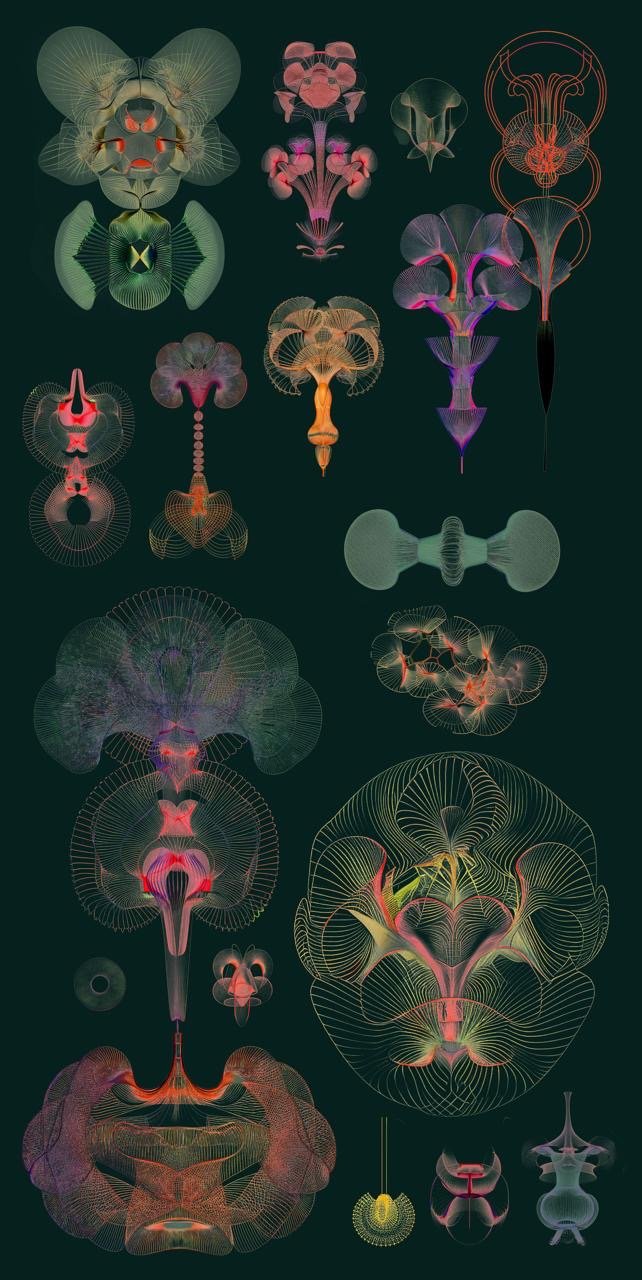

In recent years, however, the algorithm has emerged precisely as that successor. It does not replace imagology but absorbs and intensifies it, automating the production of images, preferences, and truths. The algorithm becomes the newest link in the historical chain, continuing the shift from ideology to images, and now from images to data-driven prediction — a new regime shaping how modern audiences perceive reality itself.

Content encountered through media platforms such as Instagram or X functions today much like the public opinion polls Kundera describes. The difference is that these mechanisms now transcend the geographical and social boundaries of any single society; they are fully virtual. Entering a particular algorithmic stream — marking your presence on that “island” through likes, reposts, or even the more committed act of commenting — confers a kind of membership in specific aesthetics, values, and preferences. These activities are visible to one’s followers and, in a sense, surveilled by them. Algorithmic “islands” or “algorithmology” become virtual communities formed around shared patterns of engagement, and they operate as automated imagologists: producing stable narratives and hard truths that shape perception. And although these truths emerge from virtual space, their implications are entirely real.