As someone who grew up feeling ‘uncool’, whatever that entails, to see Cameron Crowe brand himself with that very title seems paradoxical.

Crowe spent his formative years engulfed by his boundless love for music and his passion for music propelled him into the intoxicating world of music journalism in the 1970s, before a successful career as a filmmaker directing hits such as Jerry Maguire and Almost Famous. Whereas, decades later, my love for music has simply led me to spending all my money on records and concert tickets. As a teenager, Crowe wrote regular record reviews for San Diego’s underground magazine The Door, a publication with the politicised aim of acting against Richard Nixon. Soon, Crowe was contributing to Creemand Rolling Stone magazine, interviewing huge bands like the Eagles, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, and Lynyrd Skynyrd. Crowe’s remarkable accomplishments at such a young age are fascinating to read about in his new memoir and are, ultimately, cool.

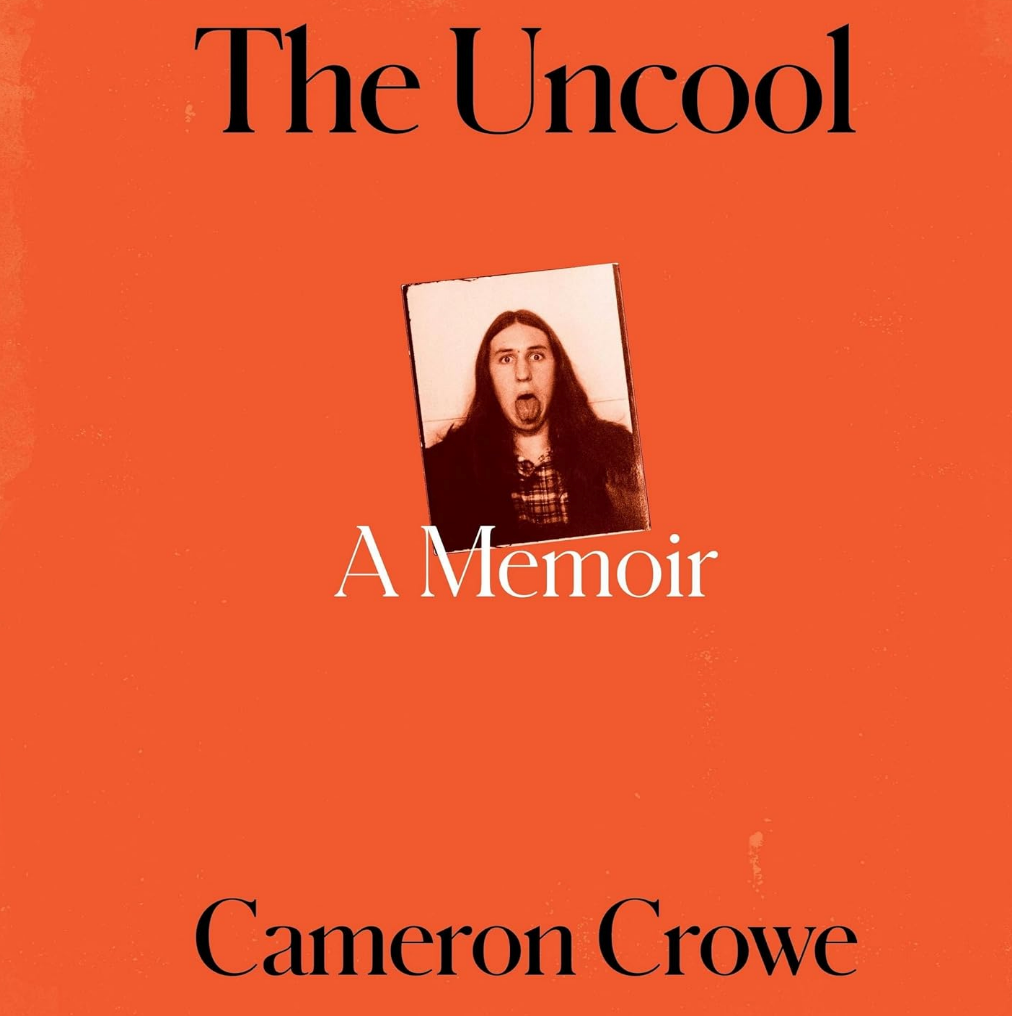

Music takes on a personified presence in Crowe’s The Uncool, something that whispers in his ear and is consistently at his shoulder guiding the way. Crowe’s writing is a love letter to music, and he never shies away from revealing his status as a fan. Crowe describes listening to music with his full heart, taking a journey with the musicians through their albums which he unpacks in his journalistic work. When interviewing the legendary musician and actor Kris Kristofferson, Crowe, aged fifteen, realises his passion for asking the artists the thingsthat he wants to know as a fan himself, sparking his “insatiable appetite to keep writing” and share his unprecedented access to musicians with the world. Crowe never stops listening, giddy and craving to uncover more, with music meaning everything to him. The Uncool is scattered with black-and-white photos, many taken by Crowe’s long-time friend, photographer Neal Preston. When a young Crowe appears in these photos, he’s gazing starry-eyed at the musicians he’s pictured with: Kristofferson, Robert Plant, Todd Rundgren, Tom Petty. Whilst many musicians saw journalists as the enemy, such as the “Rolling Stone disbeliever” Joni Mitchell, Crowe was different – a young, innocent, trustworthy fan who could coax anyone into an interview.

Permeating the memoir is Crowe’s uncanny ability to be in the right place at the right time. Aged seven, his mother, Alice, announces that she’d bought them tickets to see “a kid named Bob Dylan” at a college gymnasium. A decade later, when hanging out in Ronnie Wood’s hotel room in San Diego, David Bowie bounces into the room, leading to Crowe’s 18-monthstint for a Rolling Stone cover story with the troubled Thin White Duke himself. Summer 1973, aged fifteen, Crowe meets the real-life Pennie Lane (like Kate Hudson’s character in Almost Famous), whose real name was Pennie Trumbull, a “Band-Aide” living by the motto “only blow jobs” and who attended live shows for the music alone. Much of the memoir feels like it should be fictionalised; it is astonishingly cool that Crowe lived through these real-life events that we can only read about.

When Rolling Stones’ co-founder Jann Wenner presses a copy of Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem into Crowe’s hands, urging him to read “real writing” to become “a realwriter”, a young Crowe is inspired. “The best writing – the best music – is personal,” Wennerexplains, “and it takes a stand”. Crowe’s writing in The Uncool itself made me think aboutone of my favourite moments in Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem, when Didion reflects that:

“See enough and write it down, I tell myself, and then some morning when the world seems drained of wonder, some day when I am only going through the motions of doing what I am supposed to do, which is write – on that bankrupt morning I will simply open my notebook and there it will all be, a forgotten account with accumulated interest, paid passage back to the world out there”.

Crowe’s raw, honest memoir takes a stand as a powerful rumination on the role of music as an “emotional beacon”, transporting us back to a different world and time, like Didion’s notebooks. Crowe’s youthful world of backstage passes, late-night after show parties, hotel room hang-outs, and respectfully turning down drugs captures an extraordinary period of music that, in retrospect, is amplified to transport us back and celebrate the decades we can now only reach through music.

“A favourite song has a mind of its own,” Crowe writes, “It arrives just when you need it, and that arrival memory remains for the rest of time”. Crowe is talking about the Eagles ‘Take It Easy’ here, yet there’s a plethora of songs that he savours: Bob Dylan’s ‘Shelter from the Storm’, Todd Rundgren’s ‘We Gotta Get You a Woman’, Jackson Browne’s ‘These Days’. The Uncool is a book I escaped into, like Crowe with these iconic songs. Crowe offers a delightful, creative peek into the unfolding of his past, including surprisingly intimate moments that detail his sister, Cathy’s, struggles with mental health alongside poignant reflections on his late mother. The Uncool is an elixir, containing exceptional and precious perspectives on music, life, fame, and family – a joy to read.