Modernism emerged as a cultural force in a world still recovering from the effects of World War 1 and an increasingly industrialised world. Many writers, poets, painters and other creatives sought to reflect a civilization in moral decay, fragmented in its identity. Many of these invoked older traditions in order to subvert and revise them, reflecting the destruction of the old world and the physical, moral and ideological ruins left in its wake. However, there were a few Modernist writers who were focussed less on the destruction of the old but on the potential for the new – a chance to break away from traditions.

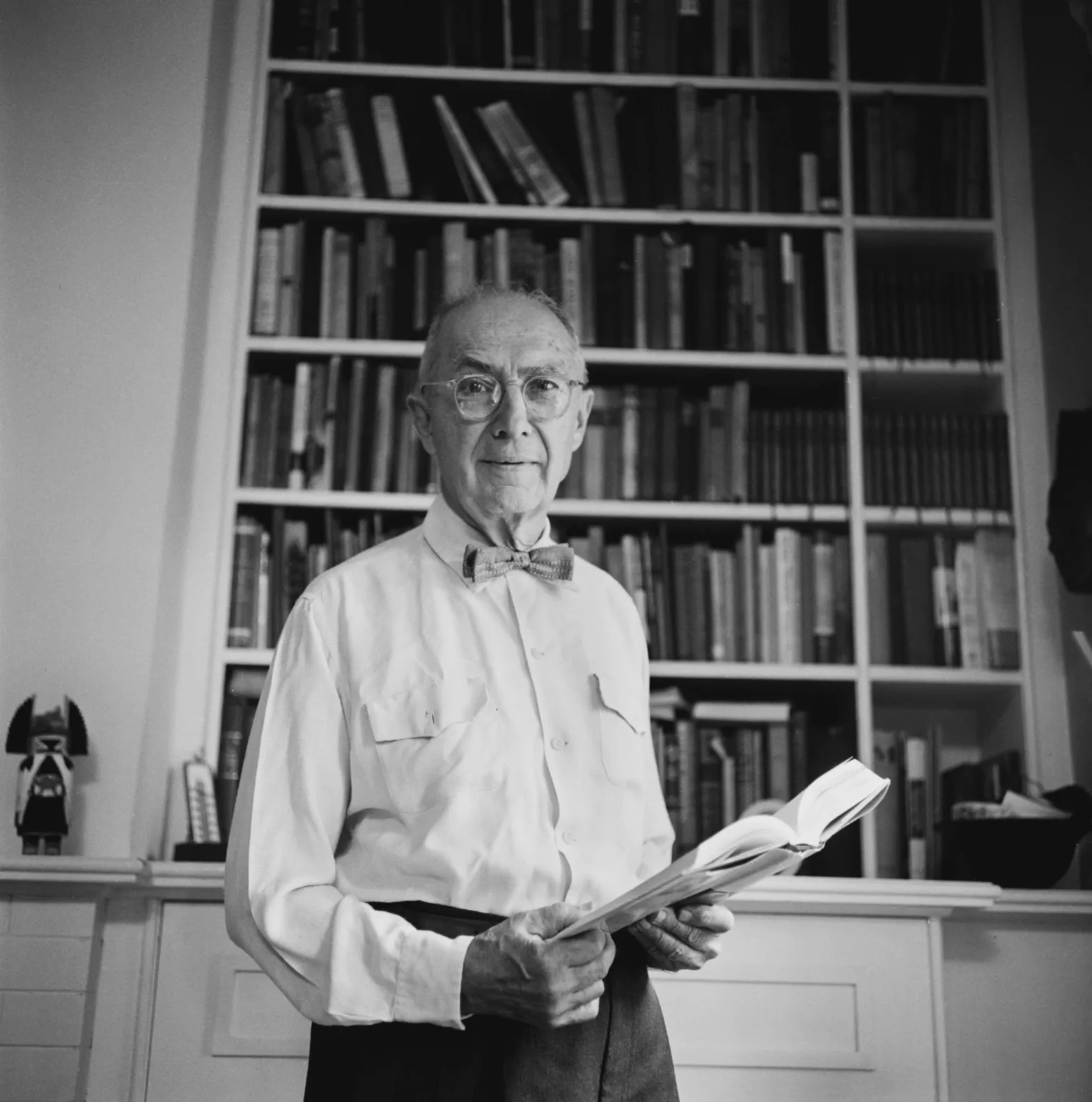

William Carlos Williams was one such writer preoccupied with the new and the now. He wanted to reflect the diversity and modern attitudes of an America still forging its national identity; a diversity that Williams knew firsthand, through his multi-cultural heritage: his English father and Puerto-Rican mother often spoke fluent Spanish and French in their household. He also saw it in his full-time career as a doctor, where he would treat a range of people speaking many dialects, day-to-day.

Dissatisfied with works that overrelied on allusion to a predominantly European literary tradition (like TS Eliot’s The Waste Land), Williams wanted instead to depict the immediate, to encourage fresh perceptions; especially of the landscape and peoples of America. Williams’ poetic intention was to create scenes ‘rooted in the locality which should give it fruit’ ie the locality of America. He placed an emphasis on ‘no idea but in things’ — depicting objects, people, places in an objective way, allowing the reader to construct their own meanings.

Williams offered his own Modernist masterpiece in 1923: Spring and All. It features one of his most well-known poems and one of the purest distillations of his poetic philosophy: XXII (known as ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’) (1923).

so much depends

Upon

A red wheel

Barrow

glazed with rain

Water

Beside the white

chickens

At just 16 words, the poem functions like a photograph or painting — precise yet open-ended, its meaning hinging on the weight of the phrase ‘so much depends’. A conceptual frame where much is left out; blanks which some readers inevitably try to fill in. What is the ‘so much’ that ‘depends’ on the ‘red wheelbarrow’? Where are the humans who use the wheelbarrow and keep the chickens? Are we on a farm or in someone’s backyard?

We also see a shunning of standard grammar — it uses no punctuation or capital letters to start each line. Although unconventional, there is a sense of structure, as well as a unique sense of rhythm. In poetry, a metrical foot is a recurring rhythmic unit of stressed and unstressed syllables in differing combinations (such as Shakespeare’s frequent use of iambic pentameter – an iamb is an unstressed followed by a stressed syllable). Here, Williams was deploying a new type of metrical unit he dubbed the ‘variable foot’. It expanded the traditional foot so that the reader varies the metre themselves based on the idiom they read the poem with.

Each brief line in ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’ is its own metrical foot, which causes a deliberate slowing down, creating a more contemplative effect when read, focusing attention on each elements of the scene in a pictorial, painterly way (the wheelbarrow glazed in rain water, the white chickens).

The characteristic Williams style, inspired by the likes of Walt Whitman and other American poets of a previous generation, became an offshoot of Modernism known as Imagism. It was pioneered by a contemporary of Williams, Ezra Pound, who coined the term ‘Make it New’ as a maxim for Imagism and even Modernism as a whole. A creed which Williams followed and realised in his work, such as in XXIII, ‘Young Sycamore’, ‘To Elsie’ and ‘Landscape with the Fall of Icarus’, among many others.

As Williams was influenced by Whitman and others to develop a new American idiom in poetry, he in turn influenced a new generation to pick up the baton. The Beat poets who rose to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s, such as Allen Ginsberg and Robert Lowell, considered Williams a key inspiration. Building on Williams’s approach, they adopted free verse and direct observation, writing poetry that captured marginalised American voices — forging a new American style. The Beats emerged during an era where American culture was spreading across the globe at an unprecedented rate. American-born arts like Jazz and comic books flourished, while Elvis and the Rat Pack became a global superstars. In his own way, Williams played a part in helping this new American identity to grow.