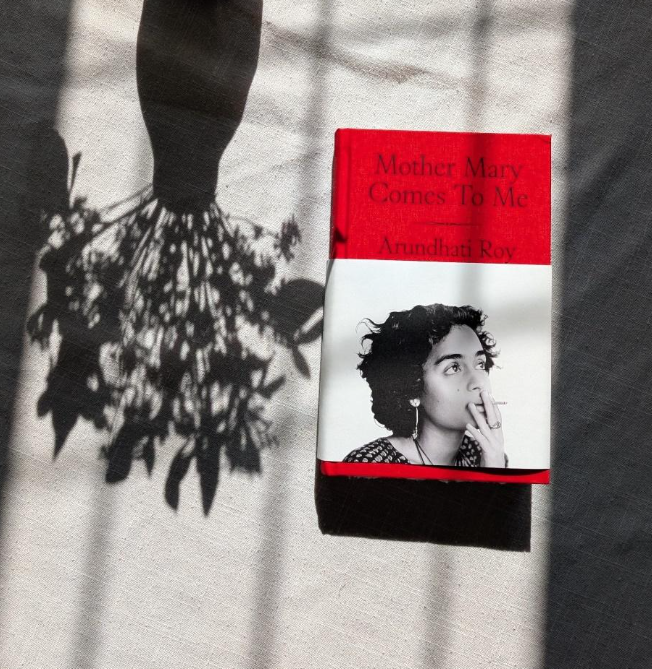

Part memoir, part obituary-of-sorts dedicated to Arundhati Roy’s late mother, Mary Roy, this somewhat holy yet unorthodox text, Mother Mary Comes To Me, redefines motherhood, all the while reforming the memoir genre. Bound by a ruby red cover and veiled with a half sleeve fashioning Roy’s portraits in young adulthood and now, this text underlines the accomplished, multifaceted authorship of Arundhati Roy. If prospective readers are to judge a book by its cover, they might presume this text to welcome aging with open arms and a healthy balance of grace, humility, pride and curiosity.

In an evening with Arundhati Roy at Brighton Dome, the author’s stage presence transpires like a kind of halo, lit up by her own light heartedness and an equal measure of intellect and sophisticated rebelliousness. A halo framed by the white scarf around her neck, embroidered with the titles of banned books in black thread. After the talk, the audience hurries to purchase their copies of Mother Mary Comes To Me before making their way to the book signing queue, where a bright light shines down on the holiest of blurbs –

“In these pages my mother, my gangster, shall live.”

Mary Roy. Matriarch. Educator. Single mother of two. Activist and advocate for women’s rights. A woman of faith, but by no means a saint. Her perhaps most defining achievement was attaining equal rights to property inheritance for all Syrian-Christian women in 1986. She put up a rigorous fight to ensure the daughters of this minority would no longer be denied their fair share in the name of an oppressive law that broke up families, banished women from financial independence, and kept a silver-spoon-sense of entitlement trickling down patrilines. She knew that this change would not only serve the women of future generations, but the brother’s, sons, and grandsons, whose ethical awareness depended on sociopolitical change. Whose personality developments had hitherto been stumped by their own patriarchal pedestal. This was a battle that tarnished her relationship with her own brother, but which boded well for the harmony between her own children.

Mary was referred to by most, including her own children, as Mrs Roy. She was also known for founding and building a school upon a hill in Kottayam, Kerala in 1967, where she was principal until 2011. A principal who favoured experience over textbooks and used Malayalam as a medium of instruction, enforcing a pride in her mother-tongue upon her students. In its humble beginnings, the school, Palikoodam, improved the lives of many. To this day, it still thrives on Mrs Roy’s visions, and is considered on of India’s best educational institutions. A school upon which Mrs Roy and her children lived, where the weight of her temper followed the non-nuclear family on their short journey home to the next room, where her unpredictable mood swings could meet and exceed their full reactive potential. Chemistry lessons taught through domestic experience, not textbooks.

Mrs Roy’s staff and students remained tentative to her strictness and tempestuous mood swings, but knew that the extent of her cruelty would be concentrated on her own offspring, and that being a student or employee was a privilege to treasure. She was ‘a queen’ because she was both worshipped and feared. Her school was a sanctuary for many but a place of confinement for two, Arundhati and her brother, whose wrongdoings in the classroom were later punished at the dinner table. Punishments which had to be compartmentalised before returning to lessons on the other side of the wall, the following day. Roy captures the chemical makeup of her mother’s personality and everything that made her who she was, to be, in essence, bittersweet. And much like the ever shifting nature of Mrs Roy’s ‘wild, unpredictable temper,’ the author recites these core memories, even the painful ones, with overriding admiration for her mother. Roy’s remarks on Mary’s aptitude for ‘bullying’ are recurrently overlayed with her capacity for ‘radical kindness,’ too.

Roy polishes these balanced outlooks by still honouring her own feelings of bitterness, detailing all the historical and still lingering sour notes with acute authenticity. Despite her emotional residue, she inflicts these pages with compassion for her late mother in untraditional, pioneering ways. Despite any resentment apparent on the page, it translates lovingly because it is honest. Like a compass, Roy’s language navigates the receiving end and root of parental cruelty, in an authorial fashion that ironizes the default, blood-tied, unconditional devotion commonly addressed to a parent, particularly one who has passed away. She maps out the narrative of her own life in relation to, and in paradoxical symbiosis with that of her life giver’s. Just as Mother Mary Roy comes to Arundhati, readers are gifted with refreshing considerations about the complicated attachments we bear to our heritage. She deciphers with us and through her mother, the crossovers between parenthood and personhood, and what coming-of-age really means. In unison, she finds meaning within her own lived experiences and signifies her mother’s legacy, untangling the cumbersome mother-daughter bond as she writes and inspecting how the meanings continue to morph, even after Mary’s death…

“That first night in a Mrs Roy-less world, I spun unanchored in space with no coordinates. I had constructed myself around her. I had grown into the peculiar shape that I am to accommodate her.”

Through converging lenses of her own lifespan, Roy entrenches the notion that we never stop growing up. That we must never cease to learn, nor discard the desire to learn. She narrates a palpable range of memories across the timeline of the book, always returning to the present after writing of the past. Childhood memories are recurrently overlayed with reflective sentiments and rhetorics that clarify Roy’s personal love of learning and implement the importance of always remaining curious. Her Mother’s Daughter. Whether in sumptuous depictions of learning to fish in Keralan rivers as a young girl; of mastering how to survive her mother’s raging tempests, both at home or in the classroom; or in climactic revisions of her runaway years, there is a childlike air of inquisitiveness breezing through these pages. Rage exists but does not dominate. Memory swims, the here and now floats above it. The motion of the text exists in a state of ebb and flow, influencing a moreish and buoyant reading experience. Even through poignant sentiments on her mother’s final days, a tender sense of humour remains bound between the book cover – young Roy and Roy now, still young at heart. Runaway rebel Roy, and Roy now, still a rebel but no longer running. She carries all the dualities attached to being her mother’s daughter with an authorial posture that is less conflicting than it is truly balanced. She eloquently revises notions of nature and nurture, symbolically investigating the individually cultivated aspects of her identity owed to umbilical severance, as well as those parts of herself she feels were passed down from her mother.

During An Evening With Arundhati Roy, the author outlines how to find this balanced attitude towards a parent who got so much wrong. A conversation vignetted throughout the text, Roy determines an authentic equilibrium between the Mother worship typical to Indian cultures, and the overly therapized language thrown around in the Western world to demonise our maternal figures all too easily. She says without saying, in her own language, that by worshiping mothers in spite of all their inevitable wrongdoings, and those which could have been prevented, we are doing ourselves a disservice, never truly serving our maternal figures in the process either. An inoffensive, inexplicit rhetoric encapsulates much of the text – something along the lines of why are we so unwilling to learn from the children we welcome to this world? Is the most enticing prospect of starting a family not to be grounded by a younger generation, whose considerations for their own future descendants will raise bars and reflexively teach us of new heights, even in our old age? Do the young not keep us in touch with the world as we no longer know it? Concurrently, Roy determines that it was her mother’s first time on earth too, distinguishing the harm she caused and forgiving her in almost the same breath, but never blaming.

They say you can’t parent your parents, but perhaps we can parent ourselves. Roy had to learn this practice independently and search for her own language ‘like a predator, in this multilingual world.’ Although her years of separation from the motherland were rooted in a personal sense of agency, leaving was an imperative choice to make. This is made explicit even in the first chapter, through a particular sentiment which propels the rest of the text…

“I left my mother not because I didn’t love her, but in order to be able to continue to love her. Staying would have made that impossible.”

Roy learnt the art of mothering with no intention of raising her own children. Having experienced her mother’s love in all its shades and temperaments, which sometimes materialised as a total lack of lovingness, if at all – Roy had long been sure that her own existence would mark the end of this matriline. Roy’s instinct to reject her birthright comes as no surprise to readers, after learning of her years of mothering herself, observing how the burden of maternity can turn a woman sour – she, both the burden and the object of her mother’s sourness. She expresses not an inability to mother, but an aversion to do so. An aversion perhaps founded on resentment, borne from being mothered then unmothered with such dailiness, or perhaps, more plausibly, in self-knowing honour of her own personhood, which she carries with a stoic, almost stubborn air, much like that of her mother’s. Her mother’s daughter – something she cyclically reminds herself through writing – free writing – like Mrs Roy taught her to do. The author’s musings on the notion of maternal instincts make way for branched discourse on the matter, and are transported to the page in a way that subverts all we think we know about what women want.

During those runaway years, Roy learnt how to be her own daughter, too. Throughout teenage chaos and young adulthood crisis’ she indirectly tended to the historic wounds of her childhood, holding her younger self, the daughter of many eras, whose sanctioned rage and wandering language had merely been waiting to be nurtured. We might ask whether it is this relentlessly tended to craft of parenting oneself which exhausts a person’s maternal instincts. Or maybe this is what inspires them.

Whatever conclusions we might draw from such a rhetoric, Roy did become a mother. Not in the traditional sense of the word (much like Mrs Roy, ironically) but a mother still. Not bound by blood, nor milk, but love. Her life partner’s ex wife died when their daughters were very young, and in her pioneering fashion, Roy made sense of maternal instincts in her own individual language. She imminently and selflessly took them under her wing, with no reliable map on how to parent. Nevertheless, Mrs Roy was Arundhati’s anchor in at least one way, having created an unwritten guidebook of mistakes to avoid repeating. Roy had no intention to be cruel, nor to try and replace the biological mother the girls had lost. As if by muscle memory, she knew how to mother the motherless, a practice that was hiding somewhere within, from all those years of mothering herself, which she did in both Mrs Roy’s presence and absence. Even after pregnancy scares, abortion, and her internal decision to never have children, she surprised herself. Roy paints her practice in mothering Pradip’s daughters to have blossomed in the same natural manner that her relationship with her lifelong love had formed and changed shape over time. A bond that was by no means nuclear, nor traditional, but entrenched in love – one that they built a home upon. A home which welcomed change with open arms and rejected tradition gleefully.

“We nailed together pieces of board and plywood to make shelves and furniture: I let our two little girls loose on it with paints and paintbrushes. Our girls. Yes. That happened naturally, like the weather.”

Perhaps it was having to invent for herself what her mother lacked which cultivated her empathy for Pradip’s children. Making up for Mrs Roy’s maternal deficiencies, the author pays homage to the girls’ pain with unconditional, uncompetitive compassion. She let them behave ‘more like animals than children’ and took their lead on forming such a precious bond that was, too, in its own right, bittersweet. A pure love, borne in the wake of their grief. When adopting this new role of mother, Roy set almost no rules for the girls. Perhaps she felt underserving of authority, or was it rather that her familiarity with maternal strictness made her averse to rules? Either or neither way, she mothered the girls on the premise that children deserve to be wild and to play. Experience over textbooks, like Mrs Roy taught her – her mother’s daughter. The only rule Roy underlined for the girls was not to call her Mummy, suggesting rather that they create another special name that only they could use. In loving synergy, the girls helped Roy to find her footing in this new maternal role, just as she helped them to find their own language, all the while, like a predator continuing the search for her own. The special name they settled on was Noonie, taken from a folk song featured in Pradip’s 1985 film Massey Sahib, which Roy had starred in. The couple’s romance began on set, and blossomed into a lifelong love where each of their respective individualities were nurtured and given space to breath. This kind of world building between two creatives clearly permeated their family life, where their girls were free to form their own identities. Roy’s prose paints a heartwarming portrait of their home life for readers to bask in between all the terse moments narrated across the memoir. Roy’s tales of her family life with Pradip and the girls, are never narrated in absence of an authorial self-awareness, however. With regards to their parenting style, she ensures to make note of various inevitable wrongdoings and those which could have been prevented.

The imagery surrounding Roy’s tales of their unique family unit is reminiscent of Tove Jansson’s Tales of Moominvalley, to draw a literary parallel. All the chaos and the unconventional coining of Noonie is seemingly evocative of Jansson’s magical creatures with quirky names, who collectively make up an untraditional but no less functional or loving family. A story world created by another pioneering writer and artist who remained in touch with her inner child throughout her lifetime. A woman whose anything-but-ordinary characters were based upon the people in her life. Whose stories made space for all of her selves, who, themselves, were somewhat shaped by her loved ones. In the same way that Jansson appoints the success of her creative practice and the existence of her fictional characters to the people who touched her life, Roy makes several implications that her writing identity was undeniably influenced by her mother.

Roy presents her corner of the motherhood spectrum in a sculpted, synchronistic writing style that adeptly subverts our preconceptions by depicting all the internal sacrifices made for the sake of her mother’s peace. She surveys her mother’s many facets and her own experience of daughterhood equally, always balancing the heavy weight of Mrs Roy’s hardships with tender attention to the wounds of her own childhood, and vice versa. To Mrs Roy, Arundhati was the valiant organ child, who bestowed that almost telepathic level of female to female empathy that can be all the more taxing when bound by blood, even against the odds of Mary’s mood. Even when it seemed Arundhati was the root of her mother’s erratic outbursts, even when she was at the receiving end of them, understanding and love overruled.

“I wanted to hug her and reassure her that everything would be okay. But you can’t hug a porcupine. Not even over the phone.”

To Mary, came Arundhati – the daughter, student, friend, and nonconsenting competitor – who learnt the household laws of remaining silent, not from a father, but a mother whom, if provoked, would be all consumed by asthma attacks as violent as her own vocabulary. Roy’s patience, her wordlessness and repressed exhales of fury, equated her mother’s oxygen. Perhaps it is this familiarity with voicelessness that can only bode well for a writing life.