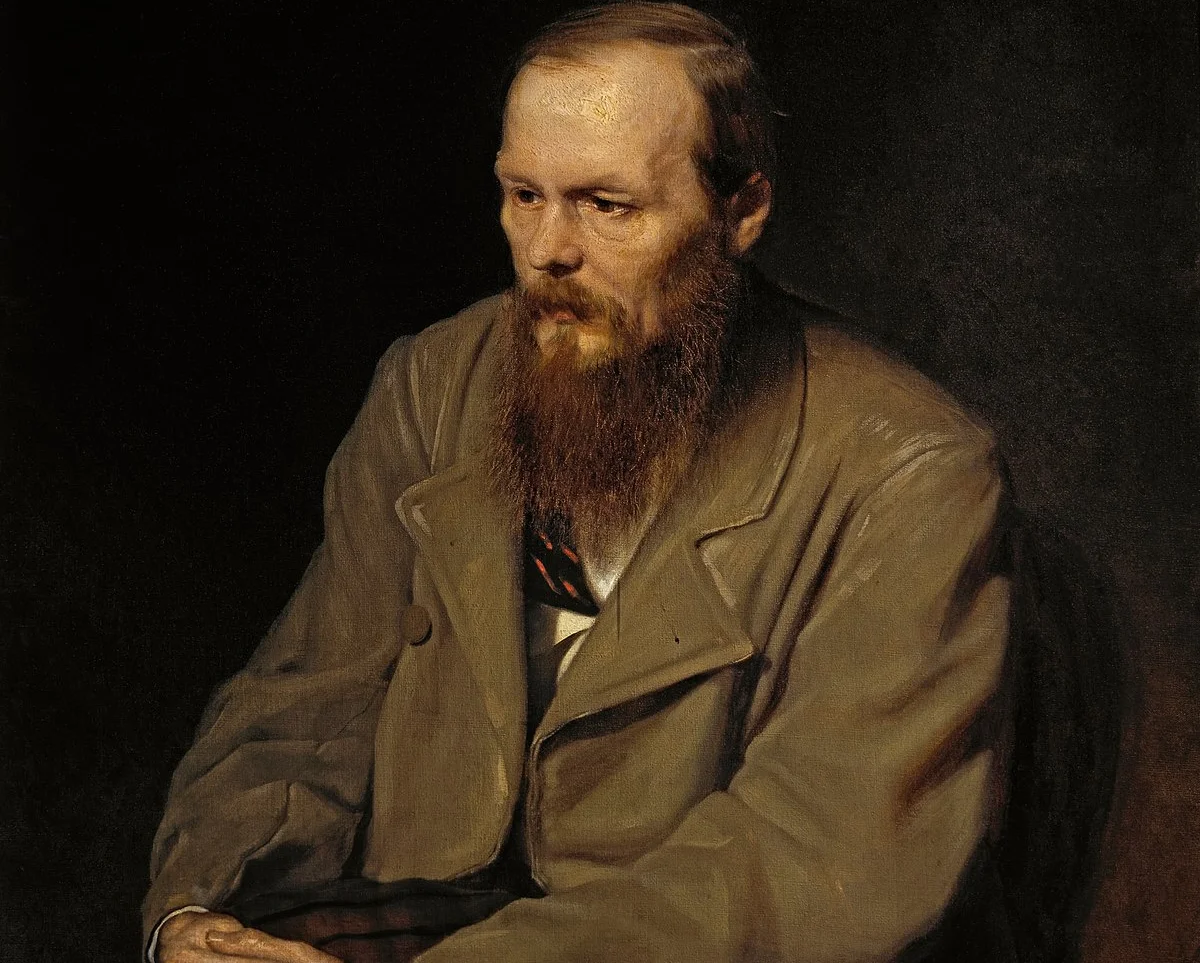

How does self-identification lead to the formation of relationships? Self-perception can be one of the most unreliable sources of one’s character; I will show how relationships are based on one’s idea of themselves, rather than who they actually are. I would like to illustrate how the ego prevents one to seek friendships of whom they admire, but rather seek those who they perceive to be on their level, or slightly below. Using Raskolnikov as my primary subject, I will be using his relationships and broken bonds to explore the power of self-perception and how it affects friendships.

Through Aristotle’s exploration of friendship within his body of Nichomachean Ethics, one can make a link between morality and ego. This section of the essay will focus on the drop of Raskolnikov’s ego, his self-perception of the self, and how he changes his social relationships to match the idea he has of himself. Perhaps, one may see that his friendships have now come to reflect his virtuous disposition, inevitably causing him top break away from his righteous mother and sister, instead choosing to befriend Sonya (a sweet but penniless prostitute). As Aristotle notes in his work, “perfect friendships are when all are alike in virtue and nature, and not through incidence”. We will now look through how he broke away from his incidental familial bond which made him depressed and erratic, to the nurturing bond with Sonya whom he may see to be alike in virtue.

Dostoevsky illustrates how a fractured self-perception can result from one comparing themselves with those who surround them, which ultimately leads them to surround themselves with people who they view similar to their disposition. From the beginning, both Raskolnikov’s mother and sister are glorified for their physical characteristics, as well as their temperaments. In Part 1, readers are given direct insight into Pulkheria Raskolnikova’s (mother) agapeic love for her children through a letter which contains many pages written to her “dear Rodya,” in which she agonises over her financial situation that has made it very hard for her to support her children and herself. She repeats how “terrible” she feels of him having to drop out of university, how she had to borrow “fifteen roubles” from a friend and could not get any more money until she paid her debts. She speaks highly of her daughter’s (Dunya) character saying, “you know how clever she is and what a firm character she has. Dunya can put up with all sorts of things, and even in the most extreme situations, she is able to find enough generosity of spirit within herself so as not to lose her firmness.” She continues speaking of her children and acts of love she hopes to bestow to them, and rarely speaks of herself. Her love for her children transcends that of herself. One may see the positive characteristics she assigns to her children to be reflective of herself. Afterall, her patience and determination to get as much money as she can to fund her children highlights a generous spirit that does not subside with the threat of poverty or the fact that she is a widow. She cleverly looks of ways to maintain herself and her children through the means accessible to her. She also describes Dunya as a “steadfast, sensible, patient, and magnanimous girl, though she has a fiery heart.” All of these can be ascribed to the mother also who presents the same steadfast and passionate traits through her letter, reminding her son to pray, and providing him with some money to help through his financial struggles.

Readers may also see a connection of their characteristics through the physical resemblance between Dunya and Pulkheria, as Dostoevsky notes of Dunya’s dazzling beauty resembling the slightly faded one of her mother’s, noting on her dark hair, slender neck, but mentions slight differences that make her unique, such as her mouth, through the eyes of Razumikhin when they visit Raskolnikov at the hospital. We are also told of the physical similarity with Dunya and Raskolnikov as in Part 1 it states that she is “a tall, slim girl being quite similar to her brother.” Here, Dostoevsky may be showing how similar all the members of their family are using physical appearance, as well as providing a means for readers to hear directly through the characters via a letter, so readers may make their own impressions on the family, without their perception being obscured through Raskolnikov’s lens. For Raskolnikov, their shared positive personality traits and appearance may be more prominent to him due to their shared gender: physically they look the same, and characteristically they hold the same self-less nature. For him, he may not view himself in the same way, even though he may share more qualities with than he is aware. Since he is educating himself despite the financial strain on his mother who views it her duty to fund him, Raskolnikov may see himself as selfish and indulgent despite his wish to fund his family in the long run; in the short term, all he sees is the hardship, stress, and sacrifice his family are making for him. On top of this, his mother writes that Dunya is marrying a wealthy man with a questionable reputation; Raskolnikov intuits it is a way for their family’s financial burden to be uplifted. Perhaps the masculine expectations at the time of men providing for their families, also weighed down on him. In the mirror, Raskolnikov perhaps sees an image distorted by expectations, guilt, and self-loathing. This image only spirals after he commits his murder of the pawnshop keeper which readers see through erratic, and impulsive decisions which will be examined in the next part of this article.

Through the murder, and the incidents which occur as an aftermath to the crime, one may look into the erratic acts carried out by Raskolnikov and seek to examine how “moral” they truly are. Through Aristotle’s idea of intrinsic and apparent goods, we will look how Raskolnikov turns into the evil creature he sees himself as. Dostoevsky demonstrates the power of the ego, and how self-perception has the power to dictate one’s path in life. We will also look how it dictates not only the choices one makes, but also the relationships they choose to nurture or dispose of.

We see Raskolnikov mourning his virtue through his response to the murder. Firstly, he rationalises murdering the pawn shopkeeper right before he does it: he justifies wanting to murder her because she is abusive to her sister, and because she sits down behind her counter waiting to profit from the “desperate”. All he wants is to get back his family heirloom and some money to help his situation. One may conclude that it is for his personal gain, however, it is fair for readers to also conclude that he did it to stop the suffering of his mother. From the beginning of the story, readers can assume that the family have been going through financial pressure since the death of his father. Not once since then, do we get an indication of Raskolnikov harbouring dark or murderous thoughts with intent to carry them out before. This can be insinuated from the physical and mental depletion of Raskolnikov who is completely bedridden from the burden of his crime to the point of his family and friends not recognising him to be as unwell in his life. One may conclude he does this from desperation, and his desperation only snowballs from there. We see this as he is hiding from the police for his crime whilst trying to make an escape, the shopkeepers sister sees him, and he has a split decision to choose what to do: confess to his crimes or kill her too. He chooses the latter. As if to resolve his guilt, he sporadically gives all his money his mother sends him to Sonya whose father is run over and stays in contact to help her family. He looks to ruin his soon-to-be father in laws reputation and thinks of even killing him to prevent his sister binding to a man he considers dangerous.

Though nothing takes away from his heinous crime, or any of the future ones he considers doing, it is important to examine Raskolnikov’s moral disposition to explain his choices of friendships and severances. Having noted that he did not commit his crime for selfish means, perhaps may take away a sense of his amorality. Moreover, his financial situation, the fact that he had to drop out from university (which was the sole reason he could not help finance his mother and sister) meant that all he was working for was useless; on top of this, he learned that his sister was sacrificing her future and life just to help fund him, and repay his mother’s sacrifice in raising them alone after their father’s death. All he sees is others sacrificing themselves for him. Perhaps that was a trigger for him to make the ultimate sacrifice. He then goes on a sacrificing spree, funding Sonya with all the money he has. One can deem his actions as involuntary, which makes him incontinent. Aristotle says, “you cannot blame an incontinent man for their actions because it is like a state of being drunk or asleep.” The concreteness of the crime makes it absurd to not put any blame on him, however, perhaps one may come to get a better understanding of him. To Raskolnikov, his actions at that moment are for a greater good which he wrongly deliberates. Perhaps looking through the Aristotelian lens, one may see this as an “apparent” good as he wrongly reasons it to be a good act. Though intrinsically wrong, Raskolnikov’s perception is temporarily blurred through his incontinence and dire life struggles. It is fair to assume that his self-perception has been low ever since he pursued his own path, as soon after, he married a very unattractive girl who was constantly ill. From this, one may psychoanalyse Raskolnikov to see himself as a sickly unattractive person, even before he committed his crimes. This led him to push away from his family, only receiving the occasional letter from them. However, after the murder, he shortly cuts all ties as soon as he can. He seeks Sonya’s company, and for her to listen to his crimes despite her not wanting to know, probably because he unconsciously sees himself as her saviour and benefactor, as well as her having to compromise her morals for her family also. There is an unspoken contract where morality, lifestyle, and status dictates Raskolnikov’s friendships. Like seeks like. This shows how one feels more comfortable to befriend those they believe to be on a similar virtuous disposition, and how one’s self-perception and ego may be flawed and lead them to act in ways to reflect their self-image.

In conclusion, Dostoevsky illustrates Aristotle’s idea of friendship and virtue very well in his literary crime novel. Through the backstories, letters, and current storyline in the lens of Raskolnikov, he presents a tale where relationships can be tracked and psychoanalysed. This aspect allows one to see Aristotle’s ethics in a psychoanalytical way which may be reflective of friendships in real life. Although this is a dramatic source of fiction, the extremities allow for readers to take themselves away from the real world and play around with the ideas of the ego, virtue, and relationships, and find the intersection in which they all collide.