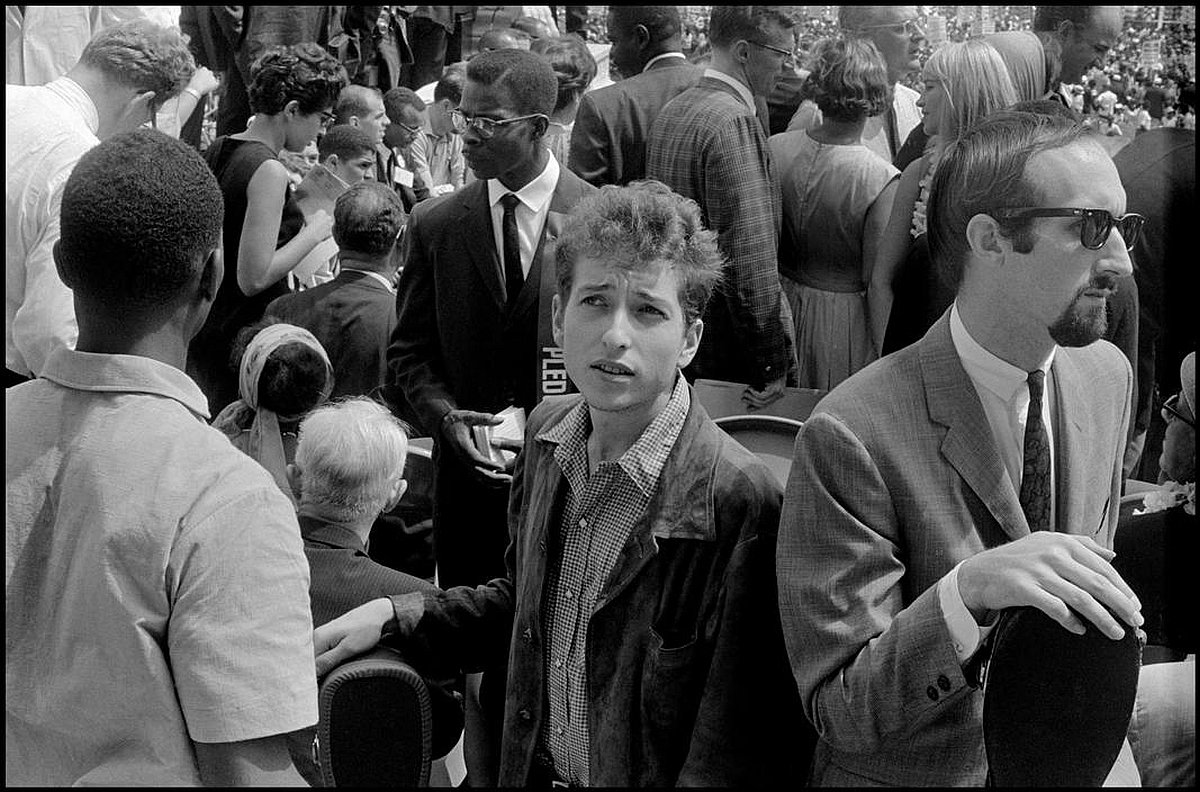

Throughout 2025, mostly thanks to the film A complete Unknown hitting cinemas and a further exploration of his career, there has been a rekindling in the interest of Bob Dylan. A whole new generation of youngsters have discovered that nasally-voiced mysterious Jewish boy who roamed Greenwich village in the folk clubs and coffeehouses all those years ago. They’re finding great joy in combing through the lyrics and tangling themselves in the ideas, emotions and poetry that Dylan creates in his music. And why shouldn’t they? Bob Dylan remains one of the greatest artists who’s ever lived, and his timeless music spans decades, just like the generations that it reaches. So why then is he so misunderstood?

The main narrative surrounding Bob Dylan is that he’s a political protest singer. We like his songs because they condemn deep injustices within our society and they galvanise us into political action. They’re revolutionary songs, songs of rebellion and insurrection, the kind that need to be sung on marches and demonstrations while we wave our banners and shout slogans through megaphones. They espouse anarchy and socialism lies at the heart of them. We then criticize Dylan for leaving his protest songs behind him, for abandoning politics for surrealist song-writing, much the same way he abandoned his acoustic music for electric folk rock. We like to ponder as to why he did this, and much of our reckoning comes down to the idea that as Dylan became more commercially successful, he became less interested in politics and more interested in making money. As he got richer, his interest in protest music faded and he was more than happy to sell out the youth movement in favour of commercialism or self-indulgence.

Here’s the truth however, Bob Dylan never was a political protest singer in the first place. I make this claim based on three observations. Firstly, if ever there was a political phase for Bob Dylan, it consisted of two albums released over the course of nine months. Secondly, there are plenty of songs on both of those albums which are not political and could not be considered protest songs. Thirdly, even the songs which could be read as political in nature often have a subtle or nuanced message, and never really go into any real depth about how he believes on the more particular issues of the day. None of these factors can equate to Bob Dylan ever being described as a political protest singer, therefore he can never be blamed for abandoning his role as one.

His first album Bob Dylan (1962) only consists of two songs written by Dylan himself, neither of which are in any way political. His next two albums, The freewheelin’ Bob Dylan released in May 1963 and The times they are a changing released in February 1964, are our only sources for Bob Dylan as a political songwriter. His fourth album Another side of Bob Dylan released in August 1964 only contains the occasional nod to social concerns of the time. The name of the album itself shows us that Dylan was moving into a different direction by this stage of time. Two albums both released within under a year of each other should hardly be enough to immortalise somebody as a protest singer. Songs like “Masters of war”, “Blowin’ in the wind”, “The lonesome death of Hattie Carroll” and “Only a pawn in the game” are undoubtedly political songs. They contain lyrics which very clearly stand as protests and invoke topical movements like the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement. But these are only some of the songs which appear on the album. The truth is, Bob Dylan always wrote music from a wide range of influences. Songs like “Girl from the north country”, “Bob Dylan’s dream”, “Boots of Spanish leather”, “One too many mornings”, “when the ship comes in” and “Don’t think twice its alright” contain no discernible political traits at all. Songs like the “Ballad of Hollis Brown” and “North country Blues” are songs about poverty and desperation, but they don’t really explain a policy which could alleviate the figures described in the songs from the hardships they face. Dylan always had an eclectic range of songwriting styles, and on both albums, you can find romantic ballads, irreverent humour, psychedelic surrealism, hillbilly country traditions and perhaps the occasional protest song in between them all. This in no way puts him in the same category as some of his contemporaries who wrote albums and albums worth of political protest music and very rarely wrote outside of that genre. This includes singer song-writers like Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Joan Baez, Ewan MacColl and Ian Campbell. If we’re honest, if we were to create a list of all Bob Dylan’s political songs, the end number probably comes to about ten or fifteen, and even that’s at a stretch. From that perspective, even Johnny Cash could be considered as a greater protest singer than Bob Dylan.

Some of the other figures involved with the sixties’ folk scene were writing songs making very obvious and very serious protests against specific wars, specific individuals and even materialism itself. Bob Dylan never writes any of his songs with any individual in mind, at least he never mentions them by name. He never specifies any particular issue; he just criticizes wider social problems of the day like racism and war. Weak tea, compared to “Tear the fascists down”, “The ballad of Ho Chi Minh” or “Eve of destruction”. He never once aligns himself with Marxism or communism, or any philosophy or ideology for that matter. The only movements he really aligns himself with these songs are the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement. Both of these were important, and indeed controversial for the middle-aged white Christian conservative audience who may well have been on the other end of the radio, but they were both movements which attracted support from liberals, socialists, libertarians and even people who no political education or philosophical depth at all, who were just sick of seeing their young men dying in pointless skirmishes or thought that Black people being treated like second-class citizens because of their skin colour was fairly ridiculous. Dylan’s more topical songs were never too dogmatic, angry and unyielding as they were. They contain more nuance, mystery and subtlety. You could argue that some of his songs aren’t necessarily political in themselves, but only become political through interpretation. “The times they are a changing” as a song has often been read as a political song, it has become a youth anthem for the sixties feeling of love, peace and tolerance. But the lyrics never specifically mention any of the changes in social attitudes that were happening at the time. It could easily just be a song about change in general, about one generation replacing another, as has happened in every era since time immemorial. Lines like “The slowest one now will later be fast” or “The first one now will later be last” may well just be about how the standards that we hold so dear as concrete truth now may well be brought into doubt in the near future. That could be about anything. Similarly, his beloved epic poem “A hard rain’s a-gonna fall” has been read by many as a nightmarish landscape of the Earth after civilisation destroys itself in a nuclear war, and the hard rain has been understood to mean acid rain. But hard rain could easily mean misfortune, hard times or difficult situations, and the harsh, bizarre imagery can appeal to anybody at any time. People have made these songs political over the years.

So why is it that Bob Dylan is still remembered as a political protest singer? Well, it’s because although he didn’t write very many political songs, the collection of songs he did write left a huge impact. Ironically, it’s because they are so subtle and indirect in their messaging, they resonate with us more than other political songs of the time. While some folk singers come across as firebrand preachers as they proclaim their stances and their outlooks from their respective pulpits, Dylan’s lyrics invite us to work out their message for ourselves. They remain with us as we attempt to decrypt them, they make our minds work in new and different ways and they leave us questioning everything, even ourselves. Let’s take an example. Phil Ochs was nothing short of a political protest singer in the sixties. Nearly every song he made was political, had a very obvious message and hammered home a very clear message about corruption, war, greed, revolution and race. He very rarely wrote an apolitical song. One of his most famous songs “I ain’t marching anymore” takes a first-person narrative of a soldier who fought in several wars throughout history. It’s an exploration of American military history, and the end result is that these wars seem futile and the soldier has had enough of being a soldier. Bob Dylan too wrote a song exploring American military history, writing about several of the same wars that Ochs does. What makes “With god on our side”so much more superior to Ochs is that it goes further. It does of course bring us the general point that wars are bad, but also casts shadow on many of the theological arguments that have been made in favour of war. It revises the self-righteous position that the USA has held when waging war, and it contains multitudes of themes like duty, patriotism, religion and conflict. Its final line poses a question to the audience, and invites us to work out the ethical qualm for ourselves. It’s a behemoth of a song.

On the 25th March 1963, Champion boxer Davey Moore’s life was cut short thanks to a controversial fight against Cuban boxer Sugar Ramos. Naturally, Phil Ochs took it upon himself to write a song about it. Davey Moore, like any Phil Ochs song,comes across as a blunt fist, almost left-wing propaganda. He very clearly takes aim at a barbaric sport which prioritises entertainment over safety, a ringside audience who egg both of them on and the “money-chasing vultures” in the gambling industry who made a fat profit out of the whole affair. Dylan’s take on the event: “Who killed Davey Moore?” takes a far more multi-layered approach. It involves several verses, all told in first person, coming from the perspective of several different people involved with the match. The referee, the crowd, the manager, the bookmaker, the journalist and his opponent. Each one of them passes the buck like a child passing the parcel at a birthday party. Dylan therein never expresses his own opinion on the matter, he only poses the question of responsibility, and he leaves it to us to make up our own mind as we untangle the ethical query, who’s fault it was, whether it was any of them or whether it was all of them. This is why Dylan’s political songs stood the test of time and struck a chord that nobody else could, they do so much more than just whinge and whine, they unlock something deep inside of ourselves we didn’t know was there. To the point where his demographic made him into the political protest singer that he never truly was. To put it simply, Bob Dylan wrote some very good political songs in the early sixties, and we remember them not because they are political, but because they are very good.

Having made Bob Dylan the very centre of the youth protest movement, his supporters then became deeply upset by the fact that he didn’t live up to the image they created for themselves. As Dylan moved away from political songwriting, the brutal reality of Bob Dylan’s writing came crashing down around the hippies and the beatniks of the era as they struggled to deal with the notion that they saw only what they wanted to see in him. They made him into something he never wanted to be and then blamed him for not being it. As Bob Dylan makes clear in his auto-biography “Chronicles, volume 1”. He was always uncomfortable with the idea that he was the voice of his generation. “All I ever done was sing songs that were dead straight and expressed powerful new realities. I had very little in common with and knew even less about a generation that I was supposed to be the voice of”. He never chose to be it, and so he never felt bad about not fulfilling his role as it. We get another clue to why he moved in a different direction in the song “my back pages”. In his reflective and deeply personal song he expresses the line “In a soldier’s stance I aimed my hand at the mongrel dogs who teach, fearing not I’d become my enemy in the instant that I preach”. Here we see Dylan showing regret for the hectoring of his earlier albums, arguing that he was in no position to make political arguments about matters he knew little about, even implying that in his messiah like manifesto-thumping he ended up becoming the kind of demagogue he was initially trying to lampoon.

The question is, should he have moved away from political songwriting? Should his writing have become more political, should it have taken on a more objective, serious and direct tone? As the sixties progressed, many different protests arose according to the new scandals of the time, the Vietnam war, the corruption of Richard Nixon, the CIA’s pestering in South America, the clampdown on the ownership of marijuana. Perhaps Bob Dylan could’ve been an important voice if he spoke out on some of these issues and joined some of these protests. The truth is however, the folk singers who did join the aforementioned protests never really changed anything, and nowadays they are only remembered for being unrealistic and utopian dreamers. Dylan on the other hand wanted his political phase to remain intact, let politics and protests be determined by the others as his music evolved and changed over the years. It’s true, his lyrics changed as he learned of surrealist poetry, but the truth is Bob Dylan never stopped changing. From being an acoustic folk singer, he became an electric rock star in the mid-sixties. Who knew, that from there he would become a deep-voiced country crooner in the late sixties and early seventies, a romantic troubadour in the mid-seventies, a born-again Christian gospel singer in the late seventies and early eighties, and yet still making it as a travelling Wilbury before that decade was out. Following his album “The times they are a changing”, the only song we could deem to be a political song is 1976’s Hurricane. As for his actions, we only see him appear now and again at a charity or a benefit gig, such as Anevening with Salvador Allende, The concert for Bangladesh, and of course, Live Aid. We can never blame him for taking on new challenges, exploring new styles and identities and constantly reinventing himself. Especially when we consider all the many musicians who trot out the same tired, stale old routine year after year. All these changes make up the tapestry of his musical career, and it’s what makes him interesting, enigmatic, pretentious, brilliant, and in a single word- Dylan.