Once John Lennon said: “You’re all freaks anyway. You’re all weirdos. But I’m free!”

And for that, he can be called a trendsetter of freedom, and as history knows, not only freedom but peace and endless lovemaking instead of war.

While the times Lennon lived through are now often described as the wildly swinging 60s culture filled with the “sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll” experience undoubtedly surging into the lives of young people, some might say that only arguable and odd things were mostly entrenched in the UK culture, affecting that generation in a disputably negative way due to the booming culture without any social prejudices.

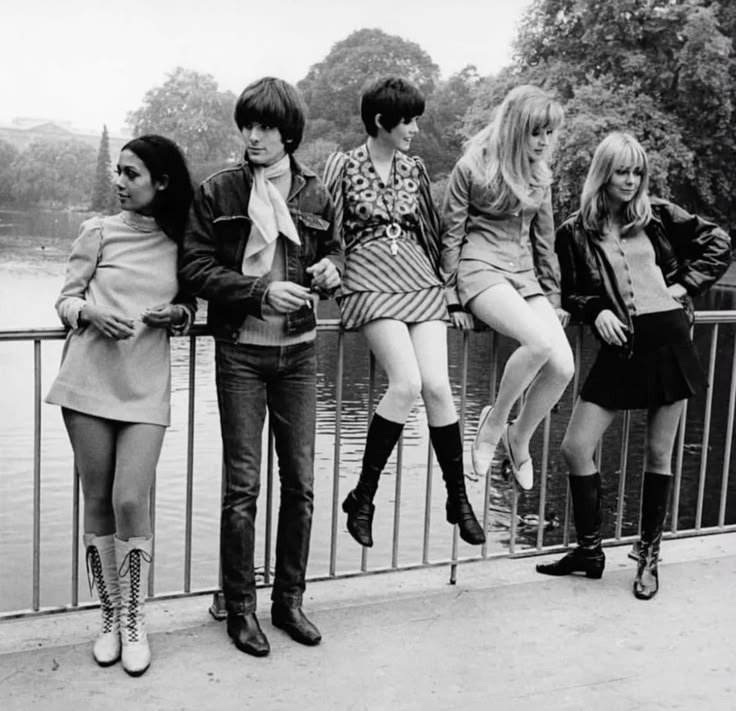

But the sixties in the UK did not only give to the world, mini skirts and the right for women to wear the desirable James Bond girlfriend bikini to the public beach.

Its main cultural headquarters, Swinging London, undoubtedly gave Britain and the whole world its own icons and places to be remembered.

In 1962, amid Cold War anxiety, the Caribbean Crisis and the overconsumerism driven by rapid technological growth across the country, Anthony Burgess published his infamous dystopian novel “A Clockwork Orange”.

Fifteen-year-old Alex, leader of a gang that terrorizes random strangers, embodies in exaggerated form the dark side of the 1960s’ booming freedom.

As a roadman of his time, he and his gang push the limits of liberty, exploring how far it can take them through violence and the chilling impunity that follows.

The Korova Café, as a place of social gathering for Alex and his friends, symbolises a rare breath of lightness, almost a sanctuary in the lives of youth during that era.

It stands in stark contrast to the lingering post-war anxiety, offering a fleeting sense of safety and freedom far from the chaotic world, where Alex’s personality is doomed to destroy.

As the main character’s story develops, shifting into drastic and disagreeable changes in other characters’ lives, Alex’s obsession with classical music, especially Beethoven remains still.

And if the Korova was a place of safe but pleasurable social escape against the backdrop of a harsh world, then music was the vital part of his inner world, trying to hint at the last bits of humanity within his violent nature.

Mirroring the cultural and social currents of its time, emphasizing a newly born, idyllic yet hedonistic way of life set against a backdrop of persistent social issues and emerging global conflicts, “AClockworkOrange”surprisingly didn’t begin as a bestseller.

It wasn’t until nearly a decade later, in 1971, that Stanley Kubrick brought the book’s film adaptation to life.

Kubrick’s vision for the outside world of the characters, their personal attributes and the color palette, which primarily consisted of crazy bright white and not fully dark but shaded black, succeeded in giving the audience a precise visual interpretation of the novel.

The signature white colour, persistent in scenes of tranquility and in the Korova Café, perfectly conveys where safety can be felt against the frequent episodes of hostility, which are reflected by the grim, faded black—the central mood of the book.

Not only did the strong visual interpretation, enhanced by slow-motion camera work to amplify the sense of endless violence and the empty, foggy London locations that contrasted with the lively, vibrant Korova stand out, but the realistic violent scenes also left a mark.

During one such scene, Malcolm McDowell, who played Alex, broke his arm. This, combined with the graphic depiction of physical abuse, contributed to the film being banned in the UK for 25 years due to concerns over copycat behavior in 1973.

Controversial as it was, the film didn’t take home any Oscars, and Kubrick himself did not receive an official Academy Award nomination.

However, his technical and artistic achievements were undeniable, placing him on the pedestal of the most recognized dystopian filmmakers of his time, further proven by AClockworkOrangebeing listed among the Top Ten Films by the National Board of Review and earning a Palme d’Or nomination at the Cannes Film Festival in 1972.

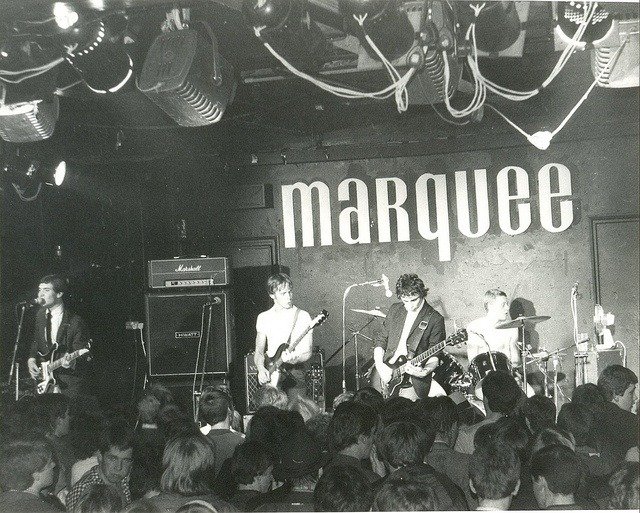

While the utopian, psychedelic Kubrick’s films played out on Odeon cinema screens, the real underground scene was rapidly spreading across Britain, becoming one of the most significant legacies of its cultural heritage.

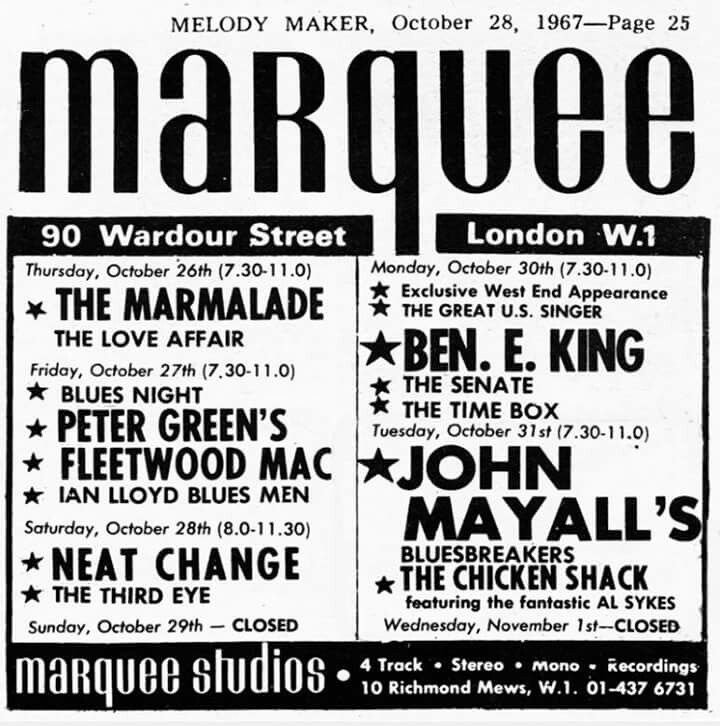

One of them, The Marquee Club, now overshadowed by the still-thriving, sugar-coated poshness of Annabel’s, was once the cradle of rising legends like The Rolling Stones, David Bowie, Pink Floyd and many others.

Nowadays just another branch of Wetherspoons, the Marquee Club founded in 1958 and originally located at 165 Oxford Street, London, became a legendary epicenter of punk and rock, fueling the rise of a groundbreaking musical wave.

Unlike New York’s Studio 54, the Marquee Club didn’t host scandalous parties, but it boldly pushed musical boundaries and experimented with song contests, daring moves for its time.

Its most notable shows, apart from early underground performances by Pink Floyd and David Bowie’s The 1980 Floor Show filmed for NBC’s late-night television, were marked by the evolution of Led Zeppelin.

In 1968, Led Zeppelin made their club debut with their well-known electrifying and intense sound experimentation, playing small gigs before launching their rise in the early 1960s.

However, in the late 1970s, Led Zeppelin’s legacy of extraordinary shows was somewhat eclipsed by the multiple explosive performances of the Sex Pistols, who challenged old musical norms with their widely recognized harsh guitar stir by the band founder Steve Jones, introducing the previously unknown punk style to the audience.

Unfortunately for the club, its pervasive drug culture, a common feature of the 1960s party scene, combined with The Who’s infamous instrument-smashing, frequent property damage and heated clashes between band members and staff, all fuelled by the rebellious spirit of emerging rock stars.

Over time, these issues took their toll, ultimately leading to the club’s closure in 2008 after several failed attempts by new owners to revive and rebrand it.

Even amid the rebellious energy of Britain’s swinging scene, where the spotlight was largely on rock stars, the modeling world quietly began its steady rise to prominence.

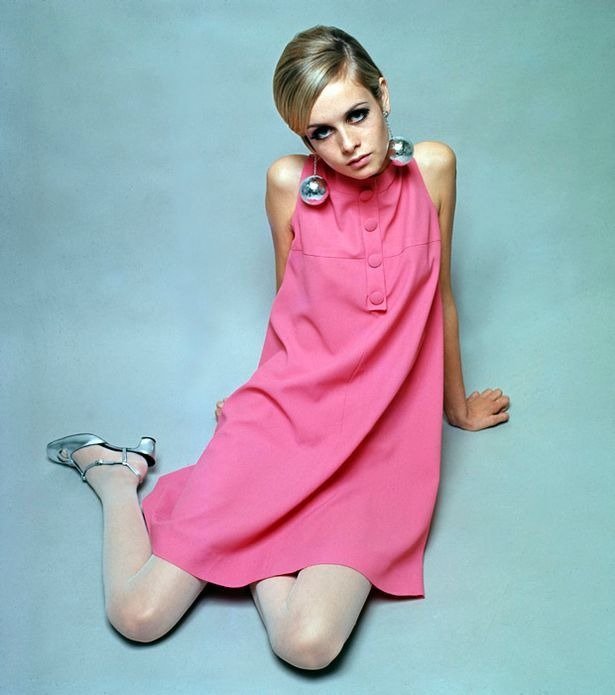

Its emblematic face was Twiggy. Now a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, Lady Lesley Hornby, she rose to fame in 1966 at 16 when featured in the Daily Express’s “The Face of ’66”, instantly becoming a symbol of Swinging London glamour and style.

To this day, her iconic bob cut, which caused a sensation on the fashion scene at the time, remains one of the most sought-after hairstyles, while her long, doll-like lashes continue to inspire beauty trends, strongly influencing major beauty industry figures such as Charlotte Tilbury, who has created multiple makeup lines and looks inspired by Twiggy’s signature style.

At a time when youthful, fresh energy was blooming in the air, Twiggy perfectly embodied it with her boyish, mischievous charm, captured effortlessly through the lenses of Vogue photographers.

Despite ongoing debates in the media today about her physical appearance, labeling it as unhealthy, similar to discussions around Kate Moss in the 1960s, she represented a completely new standard of beauty, introducing a trend for naturalness and lightness that sharply contrasted with the more seductive aesthetics of the 1950s.

Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Elle, the biggest names in fashion publishing—worked with Twiggy for decades, creating one of the most successful model-magazine collaborations of the 20th century.

She not only embodied the spirit of her era but also placed the model at the forefront, becoming the central figure rather than just a complement to the magazine’s bold branding.

Often regarded as a quintessential British pop icon, Twiggy achieved worldwide fame, appearing on the covers of Vogue US in 1967 and Vanidades Chile in 1972, highlighting her status as a global fashion figure.

With her modeling career quickly gaining momentum, Twiggy starred in the famous musical TheBoyFriend, directed by Ken Russell.

The role of actress Polly Browne, who finds herself trapped between her personal life and her character’s story, earned her two Golden Globe Awards in 1972, one for Best Actress in a Musical or Comedy and another for Most Promising Newcomer (Female).

Her charming vocal performance singing “I Could Be Happy with You” remains a cult favorite to this day.

Although the film was initially received rather coldly by critics, over time it gained recognition as a cult classic and came to be regarded as part of the golden heritage of British cinema.

In the years that followed, new icons appeared across the UK and beyond, with Jean Shrimpton standing shoulder to shoulder with Twiggy in shaping the look and spirit of the era.

The Rolling Stones were electrifying audiences with their now-legendary early performances at the Marquee Club, while American cinema began

challenging Britain’s artistic edge with films like OneFlewOvertheCuckoo’sNest(1975) by Miloš Forman.

Yet it was the Swinging Sixties themselves that left a mark so deeply engraved in cultural memory, giving the world its most unforgettable people, places and the vibrant spirit that still defines the era today.