“But man is not made for defeat” says the eponymous old man in 20th century American novelist Ernest Hemingway’s ‘The Old Man and the Sea’, “A man can be destroyed but not defeated.”

While this is one of the most famous quotes of an author revered around the world over 100 years after the publication of some of his most widely read works, it wouldn’t sound out of place in an online influencer’s YouTube video. The rhetoric of many contributors to the online world’s so-called ‘Manosphere’ can be interpreted as touching on many of the themes Hemingway explored in his vast array of novels and short stories. Hemingway is often criticised for his portrayal of women closely following the ‘Madonna-Whore complex’. Feminist theory suggests that male-written literature casts women either into the role of idyllic wife and/or mother or condemns them for sexual promiscuity and the strain this places on the men in their lives.

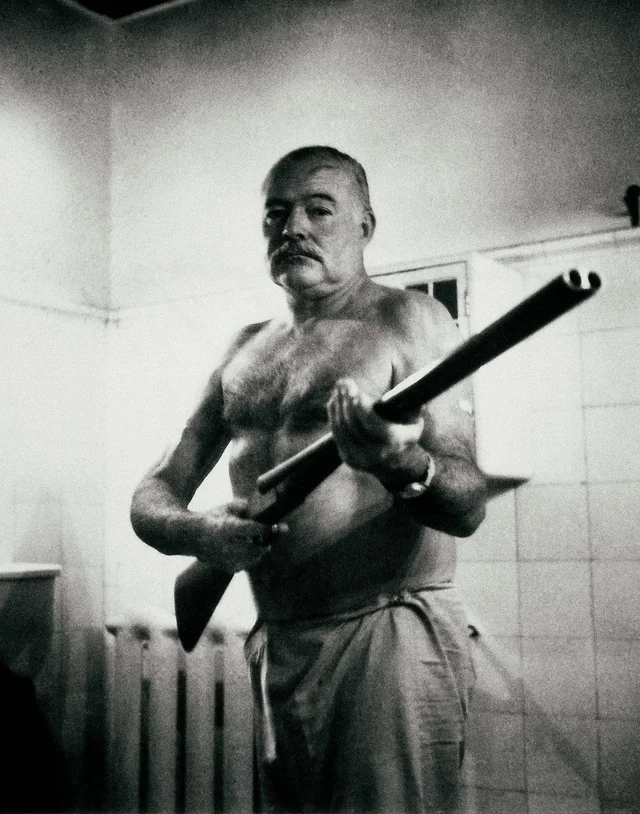

It is true that Hemingway’s works lack for female protagonists, though it is important to remember that this wasn’t particularly unusual for male authors at the time. Many of Hemingway’s stories can be viewed as providing an outlet for men who had been marginalised by society and felt uninspired by their home lives. It is exactly these men who are most heavily targeted by contemporary influencers, raising the question of how Hemingway himself would regard the ‘Manosphere’s’ appeal.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the manosphere as “websites and blogs where men express opinions about issues concerning contemporary masculinity and male relationships with women, especially those associated with views that are hostile to feminism and women’s rights.” The manosphere is of course no single entity, but simply a movement of content creators all attempting to appeal to men who feel left behind by modern society. For those creating the blogs and videos that are so widely shared, the incentive is often to sell a product, exploiting their followers’ insecurities and promising to improve their lives by selling them a protein bar. But the followers themselves are more often motivated by the communities of likeminded people that these influencers create, and the validation that can be achieved by people sharing similar experiences.

The more sinister side of this phenomenon is brought to light through the opinions that these communities often re-enforce, and that the influencers are more than happy to encourage. First amongst these is that there are fundamental and non-negotiable mental differences between men and women, far beyond anything that can be justified by any respected biological study. This is often twinned with the belief that men’s lives have been made worse by feminism, and that the problems they face have arisen through no fault of their own. Finally, the manosphere encourages men to measure their own worth in terms of physical strength, and acts of bravery; with qualities such as compassion and empathy deemed exclusively feminine traits.

The first of these points can be seen in the difference in complexity between Hemingway’s male and female characters. While widely, and rightly, praised for the depths given to many of his male protagonists, Hemingway’s female characters can come across as two-dimensional in comparison. The character of Maria in Hemingway’s 1940 novel For Whom the Bell Tolls, is a particularly damning example of this. Maria, the orphaned daughter of a Spanish mayor, exists primarily as the love interest for the novel’s protagonist, American soldier Robert Jordan. She is given very little characterisation beyond a general sense of grief for her family, and her life before the outbreak of the Spanish civil war, which drives the novel’s plot, and a desire to please Jordan. One of her last acts in the novel is to pledge lifelong fidelity to a man she’s known for three days, an act that even the most adamant of anti-feminist influencers might view as extreme.

The very same novel, however, also gives us the character of Pilar, who has established herself as the leader of a band of guerrilla fighters by the time she meets Robert Jordan. Pilar’s leadership over the group, consisting almost entirely of men, is never portrayed as particularly bad, with her calm and measured demeanour contrasted with that of her alcoholic husband, and the group’s previous leader, Pablo. Pilar is undeniably a multi-layered character, displaying poignantly human periods of jealousy and protectiveness, as well as a resolve to achieve her political goals. This contrasts completely with Maria, and the image of women as inherently passive perpetuated within the manosphere.

Hemingway’s works do often show men going through periods of emotional hardship, but never is feminism portrayed as the cause of these troubles. Hemingway was 21 years old when women were first granted the right to vote in the USA, three years before he was published for the first time. Despite this, the men in Hemingway’s works are often instead traumatised by the shadow of war. Hemingway wrote extensively about veterans of the First World War and set two of his novels within the Spanish civil war, with both conflicts portrayed as ultimately futile, and causes of great suffering.

Rarely in Hemingway’s novels, however, are the lives of his male protagonists ever made easier by women. The character of Lady Brett Ashley in 1925’s The Sun Also Rises is a twice divorced and promiscuous symbol of the increased sexual freedom of the 1920s. Brett can be seen as pitting the novel’s male protagonists against her for her own amusement, and repeatedly preventing American expatriate to Paris, Jake Barnes, from living a settled life. Barnes himself acknowledges several times throughout the novel that it is his own decision to continue to follow Brett and holds a similar view of her other suitors. This suggestion that men are ultimately responsible for their attitudes to women separates The Sun Also Rises’ portrayal of relationships from that of the manosphere’s simple mistrust of female sexuality.

The archetypal action hero that manosphere influencers promote as the ultimate form of masculinity can be found throughout Hemingway’s writing. Both Robert Jordan, and Lieutenant Frederic Henry, protagonist of A Farewell to Arms (1929), begin their novels as soldiers serving in the Spanish Civil War and First World War respectively. Both of these characters, as well as the other soldiers they interact with, often lament the civilian lives they could have led under different circumstances. Jordan especially is shown as having joined the war due to excess pride, and a desire for glory and excitement. This also acts as a key motive for the matadors that feature in many of Hemingway’s works, and often die in their pursuit of fulfilment through combat.

Santiago, the old man in The Old Man and the Sea is shown as idolising baseball player Joe DiMaggio, someone who is able to achieve the excitement of competition, and the glory of victory, without the risk and destruction of warfare. Hemingway makes his thoughts most clear in the introduction to his literary anthology Men at War (1942), here he writes “once we have a war there is only one thing to do. It must be won.” This highlights what Hemingway views as the male inability to remove themselves from conflict, no matter how well they understand the danger.

Many of Hemingway’s most resonant themes of pride, stoicism in the face of hardship, and the desire for adventure and glory; are used by contemporary influencers as a means of selling products, and perpetuating misogynist messages. Due to the success of some of these techniques, Hemingway may accept that these influencers understand masculinity, up to a point. They can’t comprehend however, or refuse to acknowledge, the need for self-awareness among men, and the inherent dangers of the qualities they wish to celebrate, that Hemingway explores so deeply. He would also be appalled at how this understanding is used to exploit men’s insecurities, rather than encourage true companionship between men.