The filmmakers behind Love Lies Bleeding (director Rose Glass and her co-writer Weronika Tofilska) are, as Glass describes “obviously … both film nerds”.

The film has a broad archive of references ranging from the works of influential queer filmmaker John Waters to The Incredible Hulk (2008). A neo-noir, queer crime thriller, Love Lies Bleeding also recalls the Wachowski sisters’ Bound (1996), and the queer-coded buddy movie Thelma and Louise (1991).

Though set in the 1980s, this pulpy romance evokes the lesbian pulp fiction – or, as founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, Joan Nestle describes it, “survival literature” – of 1950s and 60s America. These were stories in which queer women found rare representations. The film is therefore pleasurably recognisable, but also surprising – pushing boundaries of genre and representation in its visual and aural spectacular of fantasy, violence and desire.

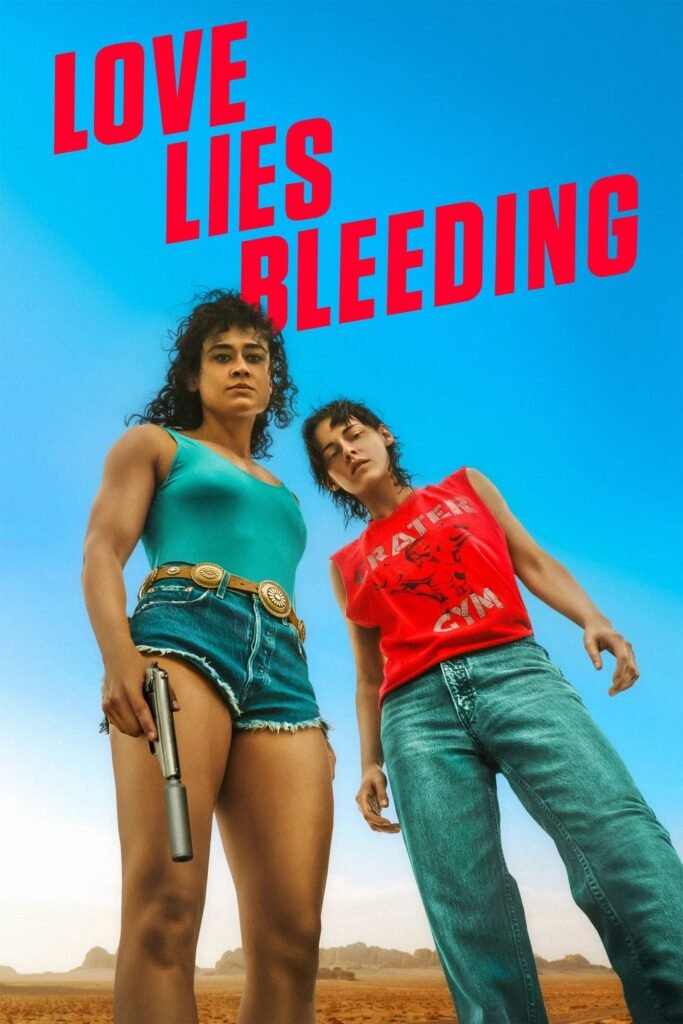

Love Lies Bleeding centres on Lou (Kristen Stewart) and Jackie (Katy O’Brian). Chain smoking, “grade-A dyke”, Lou, is isolated and stuck in a small New Mexico town managing a grimy gym owned by her estranged father – the gun-toting, bug-keeping (and sometimes eating) gangster, Lou Senior, gleefully portrayed by Ed Harris.

When Jackie passes through town on her way to a bodybuilding competition in Las Vegas, the pair are quickly drawn to each other. Lou first sees Jackie across the room of the gym. Her lingering look evokes the historic lack of queer representation on screen, which has led viewers to seek pleasure in what is suggested, rather than what is explicitly shown.

Lou and Jackie’s queer desire, however, bursts out of the subtext, taking centre stage in this chaotic romance story. Lou offers Jackie some of the steroids that come her way at the gym, and things move quickly from there. Before we know it, the pair have become lovers and Jackie has moved into Lou’s apartment (so far, so lesbian).

Like Thelma and Louise, the film is quick to confront the audience with the patriarchal violence of abusive men. In return, Jackie begins to enact her own violent punishments.

While her actions are fuelled by an increasing reliance on the steroids Lou introduced her to, both women have a rage that exceeds the chemical influence. The steroids seem to release something that was already just below the surface.

This is the rage of repeated marginalisation, injustice and indignity, both their own and of those around them. The characters are never simple avengers, however. The film consciously opts for a messier and more ambiguous trajectory for its characters than the standard “strong woman” trope. As Glass reflects, “the messy reality is more interesting”.

Certainly, the film is never boring. A visual and aural spectacular, Clint Mansell’s evocative and energising score is combined with stylised, exaggerated sound effects by sound designer Paul Davies.

This is a visceral cinematic experience, which is at once absorbing and repulsive. One pivotal scene is both startlingly grotesque and uncomfortably comical. Jackie’s muscles bulge and creak, her body increasingly and exaggeratedly powerful. This is spectacularly shown in the film’s climactic move into magical realism.

Indeed, bodies take centre stage in the film: made beautiful and abject, they are stretched, strengthened, pleasured and broken. The film’s eroticism subverts the typical objectification of queer women’s bodies on screen.

At one point Lou is shown reading American author Patrick Califia’s controversial S/M short story collection, Macho Sluts (1998). The collection is notable in part for its role in the era’s “sex wars”: described by professor of gender and sexuality Lynn Comella as “battles over pornography and sexual expression that caused deep and enduring rifts within the broader feminist movement that are still felt today”.

The choice of book is significant as it embeds the sexiness of the film in a history of queer sex and its portrayal, paying homage to its more radical predecessors.

For all its layers, however, there is a superficiality to the film. The nostalgic setting is a cliched imagining of working class, rural America and the characters are underdeveloped.

Depending on your viewpoint, the film might epitomise style over substance, or, alternatively, style as substance. Because these are stylistic choices – the film evokes a camp sensibility in its (in the words of essayist Susan Sontag) “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration”.

The performances of Stewart and O’Brian bring an intimacy that anchors the film. Despite the knowingly generic conventions of their characters, there is a sympathetic rawness to the performances that sustains our investment in them, even as we might despair of the predictable chaos of their choices.

Thelma and Louise – which was released at the start of the 1990s, just as lesbian chic was beginning to enter into the lexicon of mainstream media – played with the subtextual possibilities of queer desire. The film’s ending scene features a kiss that is possible only as death is certain, the resolution offering simultaneous liberation and foreclosure. Love Lies Bleeding avoids this tired trope. The closing shots refuse a utopian happily ever after – but tragedy is not inevitable.