How has art been used to mobilise and facilitate resistance?

In contemporary society, resistance is no longer just a political act; it is an embodied experience, that’s expressed through the body, in the sounds of protest, and in the creation of art.

Across galleries, digital spaces, and city streets, art has become one of the most powerful soft tools for challenging authority, by creating spaces for collective empathy that drive the mobilisation of communities.

From rhythmic chants, marches, and daring installations, creativity takes the forefront in shaping the perception and perseverance of progressive social movements.

Resistance

Within contemporary society, resistance manifests as a complex phenomenon typically defined as opposing established power systems, as it acts as a conduit for dissent and ignites social unrest. Its effectiveness and impact lie not only in political strategy or ideological fervour but also in the sensory and emotive experiences that animate collective action.

The fundamental connection between power and resistance is emphasised by Foucault’s (1979) famous claim that “where there is power, there is resistance.” For Foucault, resistance is a natural reaction to the abusive exercise of power, acting as a balancing mechanism. This tension between domination and defiance functions as a complex equilibrium that keepssocieties in constant negotiation between the people and the powerholders.

Erich Fromm (1992) expands on this by suggesting that resistance is maintained by empathy as much as by reason, with solidarity, love, and empathy being the foundation of connection in times of uncertainty. This raises questions about how these emotional connections may be developed to strengthen resilience and collective action.

Power of Art

Art, with its multidisciplinary nature and accessibility, serves as a powerful soft tool that transcends boundaries and encourages both public and academic participation in socio-political discourse. Whether sprayed across public spaces or curated in galleries, art is more than just aesthetics; it’s used to expose what power seeks to conceal, the truthful suffering of the marginalised and the left behind. Art disrupts the bubbles of privilege that protect many from discomfort, forcing a confrontation with the realities of inequality, suffering, and resistance. While at the same time, it offers recognition and comfort to those who live within these struggles, creating a space for solidarity.

The recent Banksy mural situated just outside the Royal Courts of Justice in London captures this tension perfectly. It’s a brutal commentary on authority and the silencing of dissent, and depicts a judge striking down a protestor. Within hours, officials tried washing it away; the irony is laughable, a piece condemning suppression was, itself, suppressed. This act of censorship has only emphasised its message.

Art like Banksy’s informs the public of issues, questions accepted norms, and fosters collective engagement. Protest art as such, occupies public spaces intentionally; it transforms streets and cities into political sites, giving opportunities for dialogue, learning, and reflection. This process showcases ‘embodied activism’, a form of resistance that intertwines individual emotion and collective experience. Sensory ethnography develops this understanding by revealing how resistance is both lived and felt. Sights, sounds, and space do not merely accompany protests but shape them. Jonsson (2021) suggests that to understand resistance, we must be conscious of its sensory properties, and to understand protest art is made up of both representation and participation.

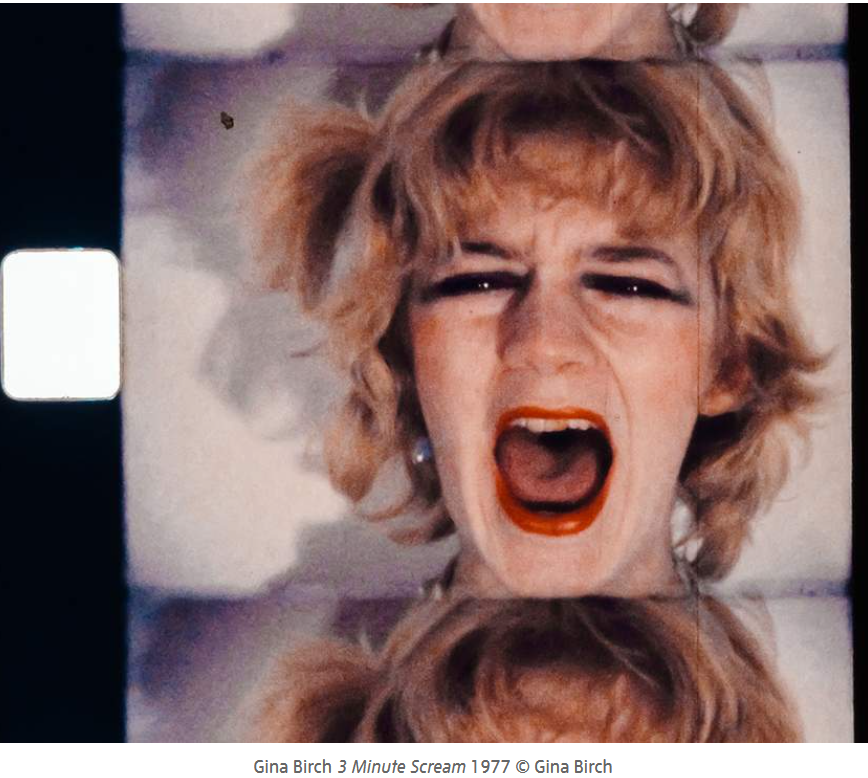

This became evident at Tate Britain’s Women in Revolt!exhibition, photography, film, documentary, and journalism came together to create a sensory history of feminist resistance. Three Minute Scream, a video piece by Gina Birch from 1977, was one of the most notable pieces. In the film, a woman confronts the camera and screams without interruption; there are no words, no explanation, only raw sound. Vibrating through the floor and into the body, the scream reverberated around the room. It was impossible to turn away. Long after I left, her scream persisted. It was more than just art; it was an audible protest and a defiance of silence. Birch’s artwork revealed the conflict between production and repression, as well as between expression and control, much like Banksy’s mural. Both illustrate that art is a living form of resistance that may be suppressed and discarded. It is precisely this tension that gives art its strength. It persists in places where authority tries to stifle it; in painted-over walls, unsettling images, and unfading sounds. Art transforms resistance from simple opposition into an act of creation.

“There is no revolution without artistic and poetic revolutions”. Brenton’s words capture how resistance is more than just a political act. Art exposes what power wants to conceal, while transforming suffering into solidarity and empathy into action, showcasing how ourbodies and actions are forms of everyday defiance. It is a means through which emotion, perception, and critiquemeet, challenging the narratives of power and making visible the inequalities and struggles of everyday life.

From Banksy’s mural that refuses to disappear, to Gina Birch’s 3-minute scream that’s impossible to ignore, art continues to show the tensions between control and expression. Through colours, sounds, and experience, it mobilises empathy and transforms individual emotion into collective movements, reminding us how creativity isn’t purely peripheral to revolution but central to it.