There are nights when the rain sounds like it’s trying to speak to me. It taps on the window in hesitant rhythms, as if unsure whether I’m listening. I slip into my darkroom with a roll of film in my pocket, nothing remarkable, just small moments I wasn’t sure were worth remembering, and close the door behind me. The latch clicks, the world softens, and suddenly it’s just me… the red hum of the safelight, and the subtle metallic stillness before anything takes shape.

People talk about loneliness as if it’s a chasm that devours you. As if being alone must mean pain, tragedy, or slipping slowly into some hollow version of yourself. And sometimes… yes, it is that. But there’s another kind of loneliness, the quiet, interior one that feels less like abandonment and more like a room inside your own chest, the one place where your thoughts resound clearly instead of drowning in the noise. I’ve lived in that space for most of my life. I wonder if most creatives have.

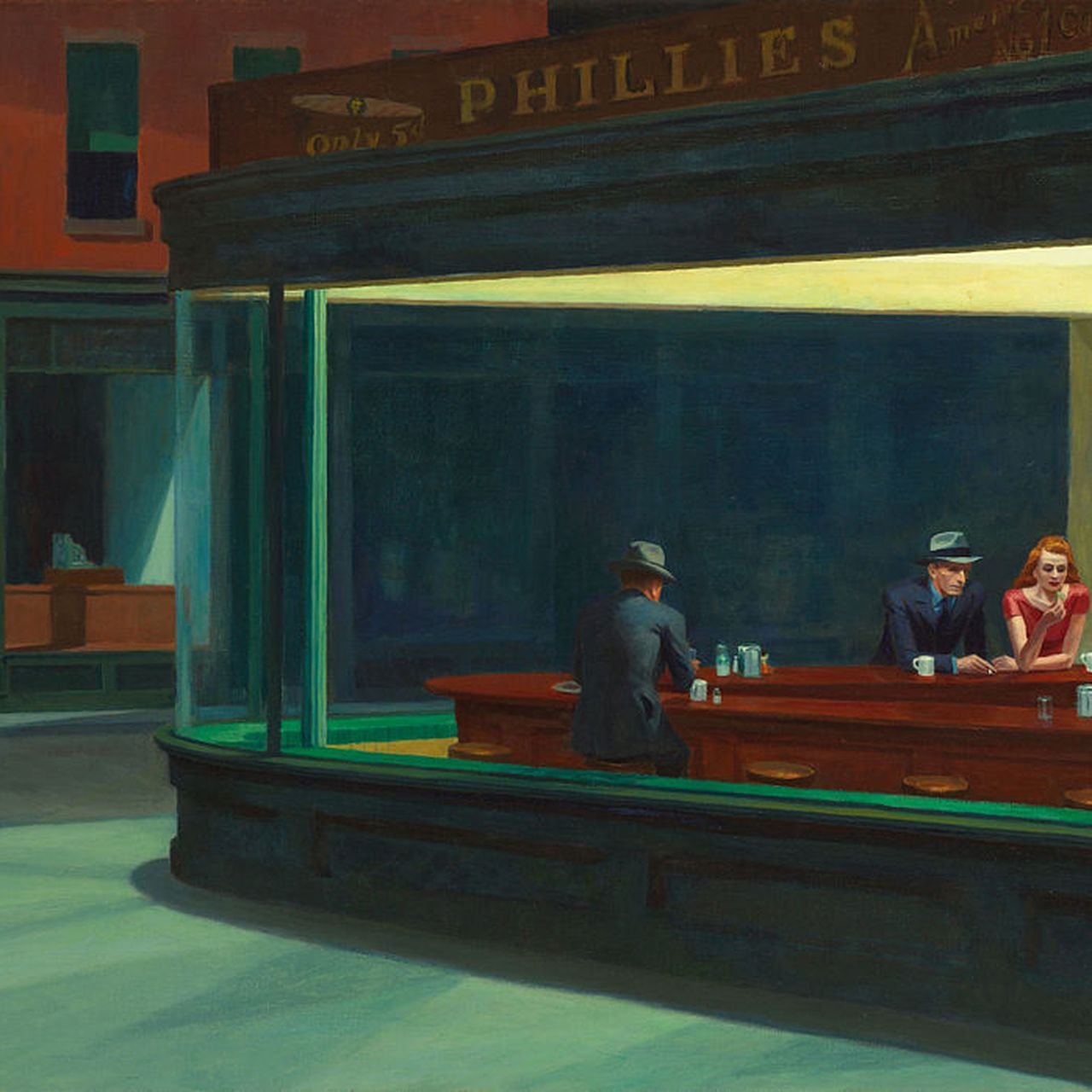

It’s strange how making art can stretch you between two opposite poles. One second you’re weightless, drifting like a ghost through a world that moves too quickly to notice; the next, creation becomes the single thread anchoring you to the earth. Maybe that’s why, recently, I’ve been thinking of Edward Hopper’s work.

Hopper, painter of empty cafés and solitary figures bathed in sedate light, understood the peculiar dignity of being alone. He didn’t romanticise crowds. He painted the pause after the conversation, the moment before the façade returns, the stillness that reveals what we try so hard to hide.

Look at Automat (1927), a woman suspended between reflection and withdrawal, her expression unreadable beneath the hard electric glow. Or Office in a Small City (1953), a man held in a room of light, staring out of a window that feels more like a threshold than a barrier. And Morning Sun (1952), a woman sitting on her bed, her body caressed gently by daylight as if the room itself is holding its breath. Hopper’s sharp geometry, wide planes of muted colour, and deliberate stillness create a stage where the inner life rises quietly to the surface.

He once said, “Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist.” It sounds simple until you realise how difficult it is to face that inner life at all.

My hands work the film onto the reel by memory. The act is meditative, familiar, ritualistic. Developing film requires patience, the kind the world no longer rewards. You can’t rush through the dark; you can’t skip ahead. You stand there, inhaling the faint chemical perfume, while the sound of the rain outside envelops you like a cocoon.

Hopper lived in that tension too… alone, but not in despair. The woman in Automat isn’t grieving, not joyful, not broken; she exists in the space between. The world doesn’t harm her; it simply continues without noticing her. And still, she sits. Breathes. Thinks. Exists. There’s power in that inner steadiness. It’s a feeling I recognise… one I think many creatives carry like a small stone in their pocket.

We rarely speak about the paralysis that comes with creating now… the pressure to be visible, exceptional, efficient. To produce relentlessly rather than feel. Even the desire to make something heartfelt becomes another battlefield of comparison. Opening yourself to art feels like stepping into a storm with nothing but a candle, hoping it doesn’t blow out before you’re done.

And then there’s grief, the silent current beneath it all. Mine, yours, all of ours. Not always raw, but present… changing the temperature of a room, altering the way light falls on the familiar. I don’t photograph grief directly, but it seeps through the cracks. It stains the edges of every frame, softens the shadows, sharpens the highlights. Hopper’s loneliness wasn’t self-pity; it was honesty. The kind that says: being alone is not the same as being lost.

The timer ticks on. I pull the film from the Patterson tank, lifting it into the faint red glow. Shadows bloom into existence… petals, faces, a skyline unfolding. Nothing monumental. Yet they are mine. Proof that I was here. Proof that something inside me insisted on witnessing the world, even when I felt like I was drifting through it.

Maybe that’s enough reason…

When I think of Hopper, I don’t see isolation. I see someone who understood the interior weather of being human. Someone who painted the silent moment before a person decides to keep going. He showed that solitude isn’t the enemy of creation, but the landscape it grows from. Not romantic, not tragic, simply true.

That’s why, on nights like this, I return to the darkroom. Not to hide but to meet myself without interruption. To sift the noise from the negative. To listen for the quiet truth that resides within all of us.

That loneliness is a language many of us speak.

That every creative person carries an invisible space inside them.

That art with soul is made by those willing to enter that room, even when it’s dim and echoing.

When the print blossoms in the tray… slow, inevitable, like something remembering how to be real, I think of Hopper’s windows. Always open just enough. Always letting the light in.

Maybe that’s all we’re trying to do really… hold the small, overlooked moments up to the light and let them speak in the silence we cannot explain.