It’s February in Rio de Janeiro, and the sweltering summer is showing no signs of surrender. “Bafado, né?” affirms Mateus, who will show me around. A lush green canopy stretches overhead, its leaves casting a dappled glow over the cobbled driveway as they soak up the morning rays.

I am at Sítio Roberto Burle Marx, the former residence and private garden of famed Brazilian landscape designer Roberto Burle Marx (1909 – 1994). Best known for the iconic wave-patterned promenade that sweeps along Copacabana’s beachfront, his landscape catalogue is estimated to number above 2,000 over a career spanning seven decades. Acquiring the Sítio in 1949, Burle Marx sought to establish a botanical laboratory of sorts to supply his flourishing landscape design business.

Over half a century later, however, is it clear that the Sítio has become something else entirely. Here, on land once dedicated to banana monoculture, Burle Marx and his team cultivated over 3,500 tropical and subtropical species, arranged into living compositions that form a portfolio of his revolutionary blend of botanical knowledge and artistic brilliance.

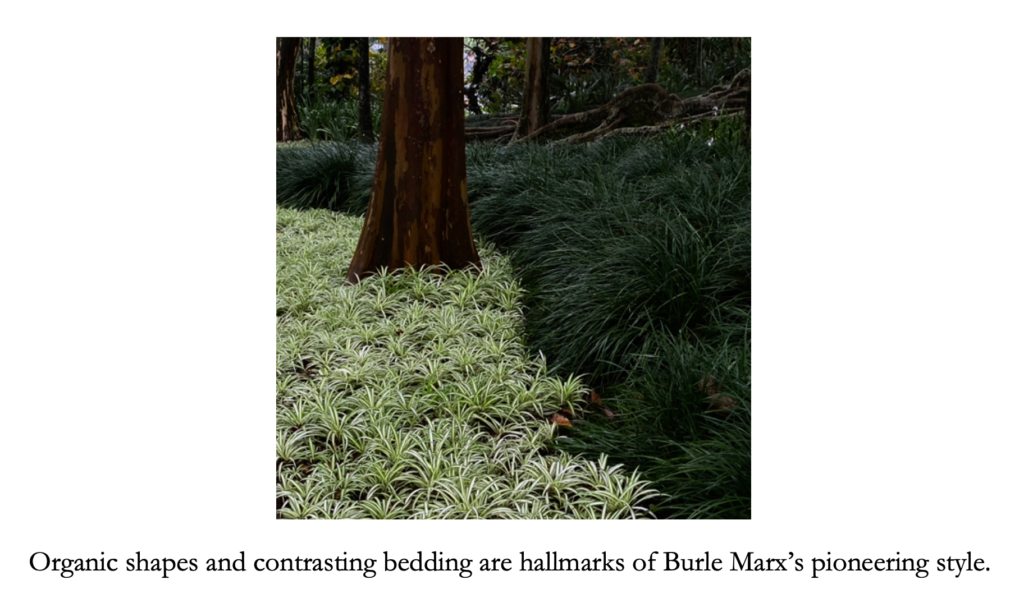

As we begin the steep approach to the main house, the path curves to the left as if to frame an enormous Ficus drupacea. Its trunk twisted and gnarled, its contorted roots resemble a hand desperately clinging onto the slope. Dark green grasses are planted around its base, lending a deep shadow to each curve and hollow. To the right stand various species of bromeliad and agave, grouped together as if to provide a spiky reminder to stay on the cobbles. The planting speaks in contrasts, with each plant’s texture, hue and value interacting like the strokes of an oil painting.

This, I had read, is a hallmark of Burle Marx’s planting. A seemingly infinite variety of forms; leaves bearing every shade of green; the thriving wilderness into which his compositional genius seamlessly blends. But theory can only take one so far. Enveloped within this living monument to tropical nature, Burle Marx’s artistic sensibility announces itself at every turn.

But this celebration of verdant abundance wasn’t always how tropical nature was understood. For centuries, in fact, it was the opposite. The very qualities embraced in Burle Marx’s plantings were read as evidence of the region’s fundamental inferiority.

As European naturalists set forth in expeditions to the tropics during the eighteenth century, their accounts cast the region as an unruly land overrun with rampant vegetation. Chief among them was Alexander von Humboldt, who documented this grim view of the tropics in over thirty volumes published following his voyage to the Americas in 1799.

His writings contrasted the ‘unsocial’ tropical landscape composed of fewer individuals of many plant species with the ‘social’ nature of temperate regions, whose environments were dominated by large tracts of single species. His language is telling; von Humboldt’s observations equated this unfamiliar flora with a lack of social order. “Man and his productions,” he concluded, “almost disappear amid the stupendous display of wild and gigantic nature.”

Affirming the tropics as the uncivilised counterpart to the temperate region, these accounts delivered a justification for European supremacy cloaked in the language of scientific observation. Temperate Europe was characterised as a place of order and restraint, diametrically opposed to the extravagant fertility of the tropics.

This denigration of tropical nature, however, was not limited to one side of the Atlantic. As von Humboldt was drafting accounts of his travels, Rio de Janeiro was itself undergoing a crisis of tropical identity. In 1816, Prince Regent D. João VI welcomed a group of French artists to the city, tasked with imbuing European ideals upon the capital of the Portuguese Empire. As city streets were razed to make room for Parisian-style avenues, Rio’s gardens began to follow suit.

Moving to Rio with his family aged nine, São Paulo-born Roberto Burle Marx encountered a city that had spent over a century trying to escape its tropical identity. With native tropical species largely confined to botanic gardens to be cultivated for economic ends, parks and gardens were filled with roses, daisies and dahlias in imitation of temperate gardens.

With a passion for painting from an early age, Burle Marx’s botanical revelation came not in Brazil but during a trip to Berlin as a teenager. Visiting the Dahlem Botanic Garden, a display of Brazilian flora awakened his horticultural curiosity. Why were these plants showcased in German hothouses while all but absent from gardens in their country of origin? Returning home, he began to plant native species in his family garden, experiments that caught the eye of neighbour Lúcio Costa, titan of Brazilian Modernism and future architect of Brasília.

Invited aged just twenty-one to compose the garden of a home Costa had designed in Copacabana, Burle Marx quickly gained notoriety for his innovative approach to planting. Once-neglected species such as cacti and bromeliads took centre stage, while smaller bedding plants were arranged in sweeping organic shapes that stood in stark opposition to the imported formality that had dominated Rio’s planted spaces. This was the primordial form of the modern tropical garden, Burle Marx’s most celebrated creation.

This brings us back to the Sítio. The property, long since outgrown from its utilitarian origins, stands as the masterwork of Burle Marx’s unbridled creativity. If the modern tropical garden is his signature style, the Sítio is his magnum opus, the culmination of five decades of rigorous experimentation and joyous expression.

Continuing our climb beyond the monumental Ficus, stone steps usher a meandering path away from the driveway and through yet more distinctly prickly individuals. These plants are well-suited to the drier microclimate of this west-facing slope, conditions strikingly different from the humid Atlantic rainforest visible beyond. It was this ecological variance that drew Burle Marx to the Sítio, allowing a wide range of species to exist within their ecological niche.

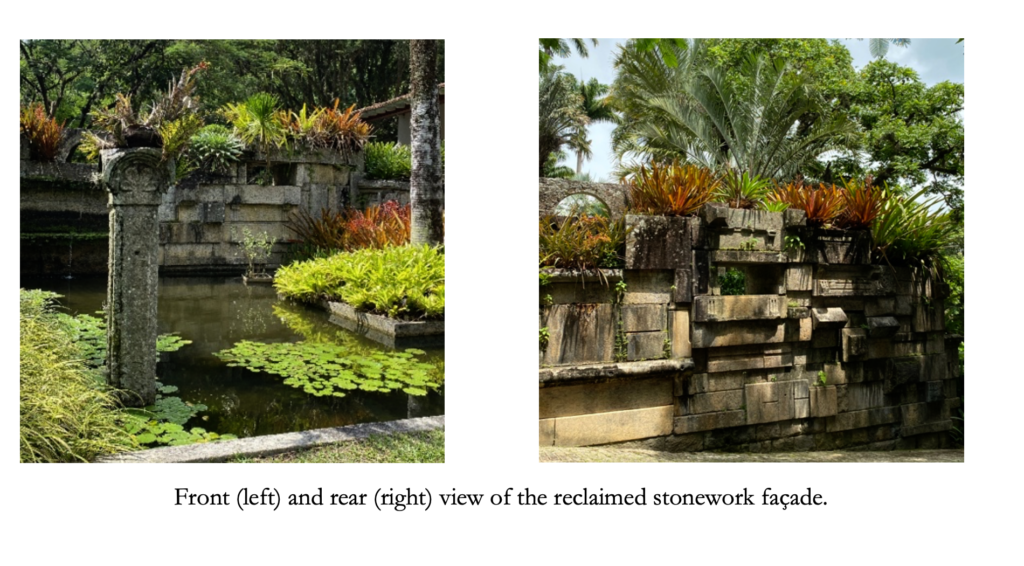

The steps soon reach a lawn, my entry flanked by two towering specimens of imperial palm (Roystonea oleracea). To my left, a pond edged with stonework salvaged from buildings demolished in Rio’s city centre immediately draws focus. Repurposed into an abstract mural, these colonial-era fragments are made to form patterns that feel timeless, even ancient, though an artefact of some long-lost civilisation.

In many ways, this lawn presents a microcosm of Burle Marx’s philosophy. Whether championing native plants or salvaging architectural fragments discarded from demolitions, his work so often contains a reverence of that which has been dismissed. Yet this restorative ethic is only one aspect of his vision. Around the courtyard, another defining principle takes form.

Opposite the pond stands a ten-foot totem by artist Miguel dos Santos. Entitled Yorubá, it bears forms rooted in the West African culture from which it takes its name. Overlooking the lawn is a small Catholic chapel, painstakingly restored to function by Burle Marx in the 1970s with the help of Lúcio Costa. These distinct monuments of spirituality stand in dialogue, forming an architectural ensemble characteristic of the heterogeneity that animates Burle Marx’s built and botanical compositions.

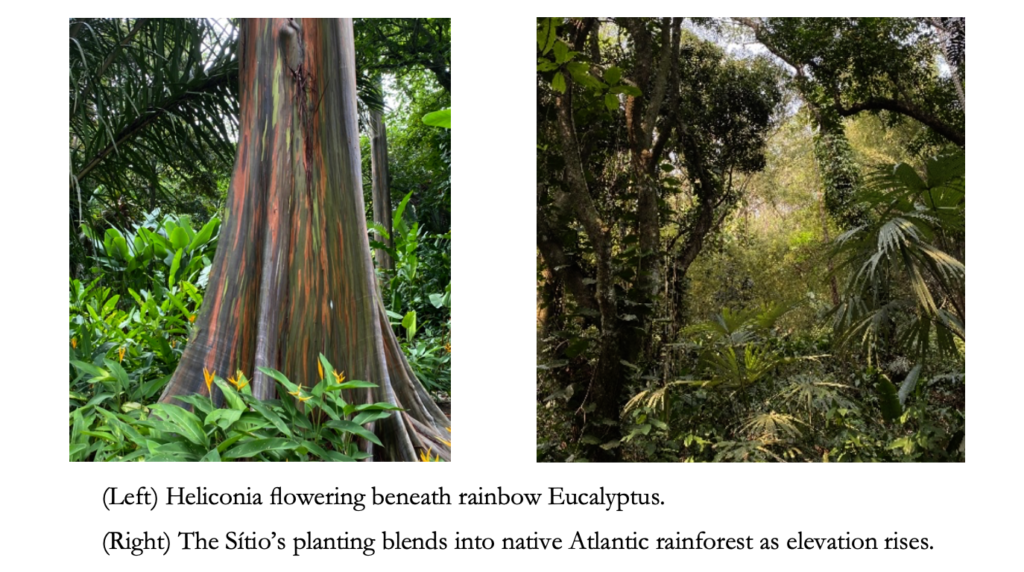

Continuing through the lawn and climbing higher along the driveway, this diversity intensifies through an increasing abundance of tropical species both native and exotic. The fiery orange inflorescence of Heliconia endemic to this region of Brazil complement the mesmerising multicoloured bark of the rainbow Eucalyptus originating in the Philippines. Clumps of blue bamboo are dwarfed by towering açaí palms laden with dark purple fruit. Above one hundred metres’ elevation planting ceases completely, as the Sítio’s lush planting blends into flourishing Atlantic rainforest.

Burle Marx’s influence, like his plantings, refuses clear boundaries. One does not have to travel far to see evidence of his profound impact. In nearby neighbourhoods of Western Rio, approximately three hundred horticulture suppliers stand testament to his continuing legacy. These tropical nurseries, affectionately referred to by Burle Marx as ‘satellites’ of the Sítio, were largely established by gardeners who had hones their horticultural knowledge at the property. A region once dominated by banana monoculture is now synonymous with the production of ornamental tropical plants, as the tropical species once dismissed and denigrated are cultivated for appreciation.

The Sítio, in essence, is far more than a garden. Nor is it simply a sanctuary of tropical nature. It speaks of expression in the fullest sense of the word, of a harmonious blending of the built and the botanical that is more than the sum of its parts. Best understood as a living sketchbook, the Sítio represents an ongoing collaboration between an artist and his medium, a monument of creativity that continues to evolve as its plantings mature.

Far from having tamed this tropical nature, Roberto Burle Marx’s genius has invited it to flourish.