“Drugs, crime, sex and absolute debauchery” said the expectant moviegoer. “Screen 1” replied the dazed usher – a brief interaction that may very well have occurred between 1981 to 1993 just around the corner from King’s Cross station.

Why may this have occurred? Well because Scala cinema was the ultimate cinema of sin.

Founded by Stephen Wooley in 1979, originally on Tottenham Court Road subsequently moving to King’s Cross two years later into a concert venue that previously housed an indoor forest for primates, the cinema opened with a screening of King Kong, a fitting ode to the past and a suitable hint of things to come.

Woodley, eager to create the UK equivalent of the eclectic grindhouse scenes of Los Angeles and San Francisco, managed to take things a step further going to the eclectic extreme in fact, and located in a neighbourhood populated by prostitutes and drug addicts only added to the allure. The Scala was just a few steps away from The Bell, one of London’s most popular and influential mixed lesbian and gay venues. Post-Earls Court and pre-Soho, the King’s Cross of the 1980s-early 1990s was an LGBT+ haven. A far cry from the King’s Cross of today.

Former programme manager at Scala and now head of video and distribution at The British Film Institute, Jane Giles told the Guardian “It was a thrilling experience, part of that thrill was that you walked out [of the station] into the badlands of King’s Cross. You then quite quickly found your way to this palatial building, like some sort of bonkers white castle that you see on the logo of Disney. Going up the marble staircase led you into this massive space. The rake was very steep, the seats bolt upright and I think you sat there for a moment with a sense of incredible anticipation. In addition, the auditorium was dark and, at times, illicit. There was a frisson. A lot of the films were quite explicit, so there was a sexuality about the place that was unusual in cinemas. It all added up to an incredibly potent combination.”

Wild stories about those Scala days are innumerable, showcased in the recent documentary, Scala!!! Or, The Incredibly Strange Rise of the World’s Wildest Cinema and How it Influenced a Mixed-Up Generation of Weirdos and Misfits, presents an array of wonderfully atrocious and astonishing accounts and occurrences that safety inspectors today would have nightmares over.

In the doc, employee JoAnne Sellar describes clearing the cinema the morning after one of its legendary all-nighters and finding a dead body (“He was still warm, but very stiff”). The antics at the gay-themed all-nighters: “We had to try to explain to Serena the cleaner why there were so many used latex gloves on the floor after a lesbian all-nighter,” said Giles. “I told her it was a fashion statement.” The dope-fiend projectionist who scratched a CND symbol into a Pearl & Dean army recruitment ad and got the reels in the wrong order at a horror festival…

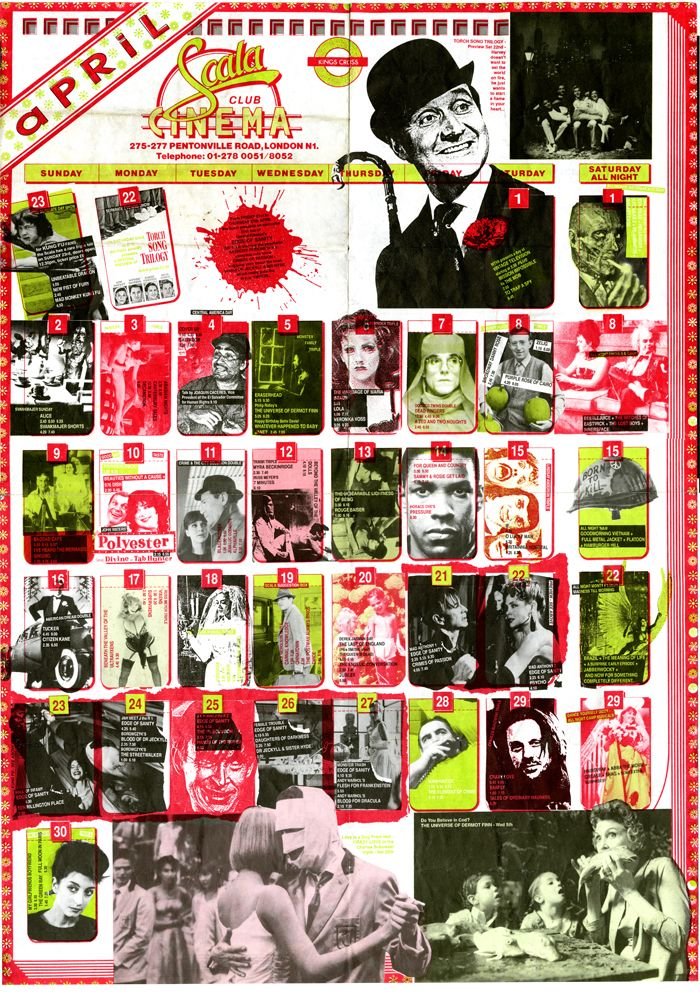

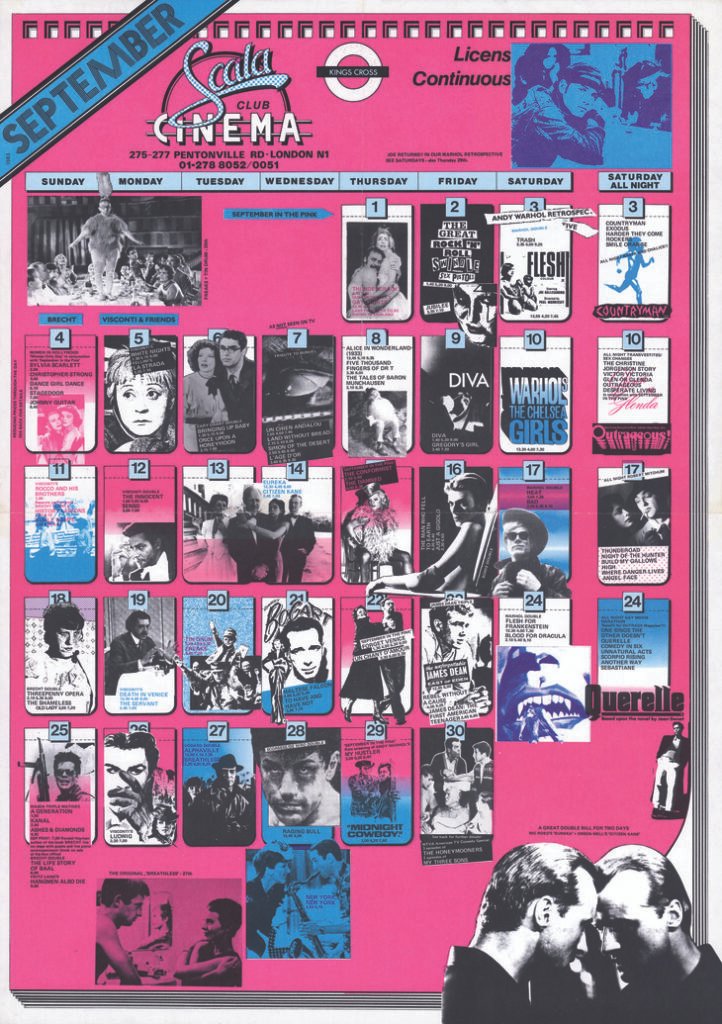

Within the famously cold and uncomfortable venue the showings were a fusion of masterpiece and porn, arthouse epics from the likes of Ingmar Bergman and Werner Herzog rubbed shoulders with sexploitation romps such as Curt McDowell’s infamous semi-porn comedy horror Thundercrack! and John Waters’s 70s trash trilogy Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble and Desperate Living. These were films other venues simply would not screen, forever nudging the boundaries of convention.

Recalling his sole visit, John Waters, the Scala’s “patron saint” said “It was like joining a club, a very secret club, like a biker gang or something. I remember the audience was even more berserk than any midnight show I had ever seen in America. Maybe they were on ecstasy, I don’t know, but it was a really raucous audience. It was so great – but it was almost scary.”

Over the course of a decade and aside from the debauchery for which it is primarily considered, an accidental counterculture emerged in what is seen as Britain’s post-punk Thatcher years. The physical space enveloping the chaos became a cultural space in which audiences became productive creative communities…

However, just like the youth culture of the time to what it is today, outside those physical walls change was imminent. The surrounding area in the 1980s was medieval and just getting to the cinema in one piece could be a challenge. But the times were changing and as rundown as it may have been, developers had their eyes on the location. “There’s a crowd scene in the film and you can literally see a red cross on the wall,” says Giles. “It wasn’t graffiti, it was something to do with the redevelopment of the area.”

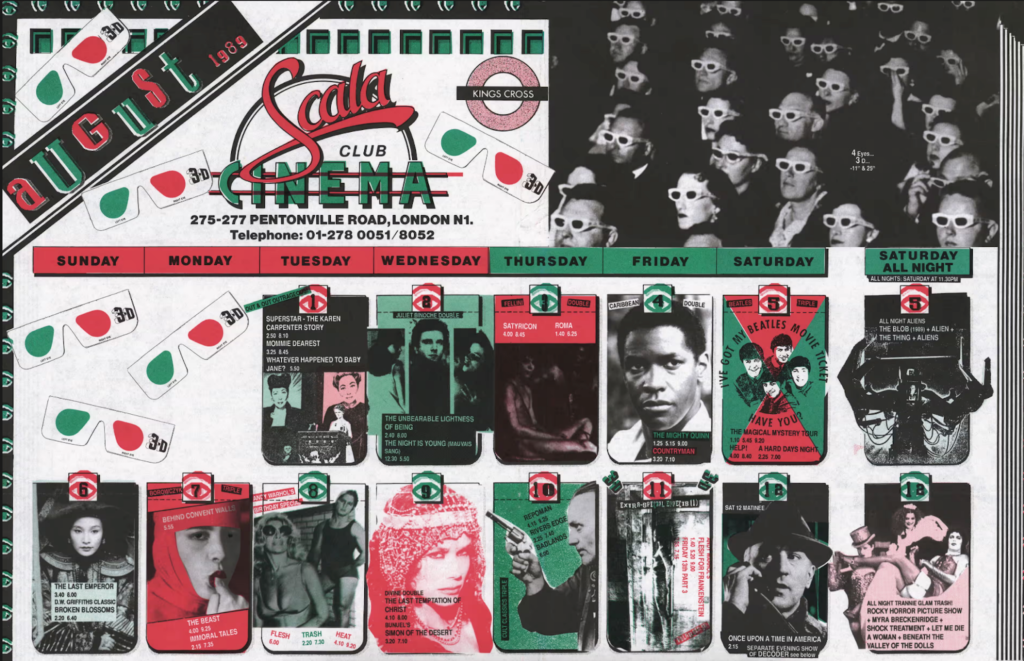

In the end it was film studio Warner Brothers that proved to be the demise of Scala. In 1992 the studio was tipped off about an illegal screening of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, outlawed in 1974 after a spate of copycat teenage violence, and a legal case ensued, which Giles, who had left the Scala by this time, returned to fight. “They’d never had a theatrical case before and it was quite sexy for them,” she recalls. “But it wasn’t at all sexy for me.” The Scala lost the court case and went into receivership and the last of the cinema’s monthly film-strip style calendars, the format of which has been lovingly reproduced for Scala Forever, was printed in May 1993.

The loss is more profound and wide-reaching than simply that of a cult cinema. In many ways, an institution as wayward and reckless as the Scala feels like a relic of a different era, at least in terms of existing in the centre of a major UK city.

“When you think about other cultural spaces, there were barriers,” said Giles. “Intellectual barriers, sometimes behavioural barriers, sometimes age barriers. People who were not feeling at home in their skin, in their life, found in the Scala a peer group, an audience and a programme that had an appeal to them.”

Outside the virtual realm, the economics of modern urban life make such quixotic ventures sadly almost impossible nowadays, this magazine is one of them! But abandoning them means the risk of abandoning something important. As Rory Perkins, one of the Scala’s regular DJs puts it: “The Scala became us. And we became it.”

Following the success of the documentary, Giles remarked: “You can always tell a Scala person by the way their eyes light up and they laugh at the memories. But alongside them is a new audience, young people gripped by the very idea of a rock ’n’ roll cinema that was a pirate ship on the stormy seas of Thatcher’s Britain and taking that inspiration forward into their own lives.”

Scala will be remembered as more than just a cinema, but a period lost in time.