It’s never been easier to watch movies. Fire up your streaming service of choice, navigate through pages of straight-to-Netflix slop, and enjoy the show. Yet, prior to the mid-2010s, streaming content was a novelty; further back than that, the concept of unlimited access to media at home was a sci-fi dream. Indeed, commercial VHS players didn’t reach the United Kingdom until 1978, over 80 years after the first cinema screenings for a paying audience, and offered only a fraction of film and TV history—often at extortionate prices. As the historian Dominic Sandbrook points out “in a weird way, whether they [episodes of television] were in the archive or not didn’t really matter, because you didn’t see them anyway” in the days before home video.

Nonetheless, the archival status of film remains a crucial factor in the world of media consumption. About 90% of silent films are assumed to be lost, some in fires due to their chemically volatile filmstock, while others were purposefully recycled to regain trace amounts of silver for resale. Yet tantalising traces of these cultural artefacts are sometimes found, often in the strangest of places—as in 2023, when a fragment of the lost 1917 movie Cleopatra was discovered in a toy projector being sold on eBay. It’s no surprise, then, that the potential for cultural treasure hunting has attracted numerous would-be Indiana Joneses over the decades. What is surprising, however, is the recent boom in interest in the concept of lost media, fuelled by countless YouTube videos, podcasts, and social media posts, and the fact that it seems to primarily excite those from younger generations.

The Lost Media Wiki, founded in 2012, catalogues “pieces of lost or hard-to-find media; whether it be video, audio or otherwise […] if it’s completely lost or simply inaccessible to the general public, it belongs here”. Notable films documented by the website include the presumed-lost London After Midnight and the missing Alfred Hitchcock pictureThe Mountain Eagle (both 1927), although there are also extensive entries detailing alternate versions of commercially available films, such as lost cuts of Blade Runner (1982) and King Kong (1933). Yet this definition of lost media as content “simply inaccessible to the general public” is a murky one, covering everything from big-budget movies to long-forgotten Minecraft streams buried in the depths of the YouTube algorithm. The Lost Media Wiki even has pages dedicated to content as mundane as lost BBC2 ident cards—just what is driving this spike in interest in our cultural past?

Of course, there have always been film collectors, and we owe the existence of much early cinema to their (in fact frequently illegal) practices. In 1974, the home of actor Roddy McDowall was raided by the FBI, who sought to press charges against him over his sketchily acquired archive of over 1000 film and television prints. McDowall avoided criminal charges by providing information about his black-market contacts, highlighting the underground nature of film trading at that time. Luckily, the emergence of the home video market has democratised access to media. However, despite these positive changes, archivists’ desire to see rare or even unavailable media remains, as does a culture of false information, backstabbing, and gatekeeping. Perhaps the most infamous example of this relates to the melodrama surrounding the hunt for the pilot episode of The Backyardigans, a Nickelodeon pre-school programme, where individuals involved in the search effort fabricated false leads and spread misinformation to conceal the pilot’s existence from one another. What could possibly motivate such obsessive behaviour over something so seemingly banal?

Perhaps the easiest explanation is nostalgia. It appears to be no coincidence that many lost media search efforts focus on television and films watched during childhood—not a day seems to go by without discussion of lost Spongebob Squarepants episodes or, in the UK, missing Doctor Who serials from the show’s early years. While these may seem frivolous subjects, it’s important to remember that one man’s trash is another man’s treasure; the pertinent question relates not to what is being searched for, but why.

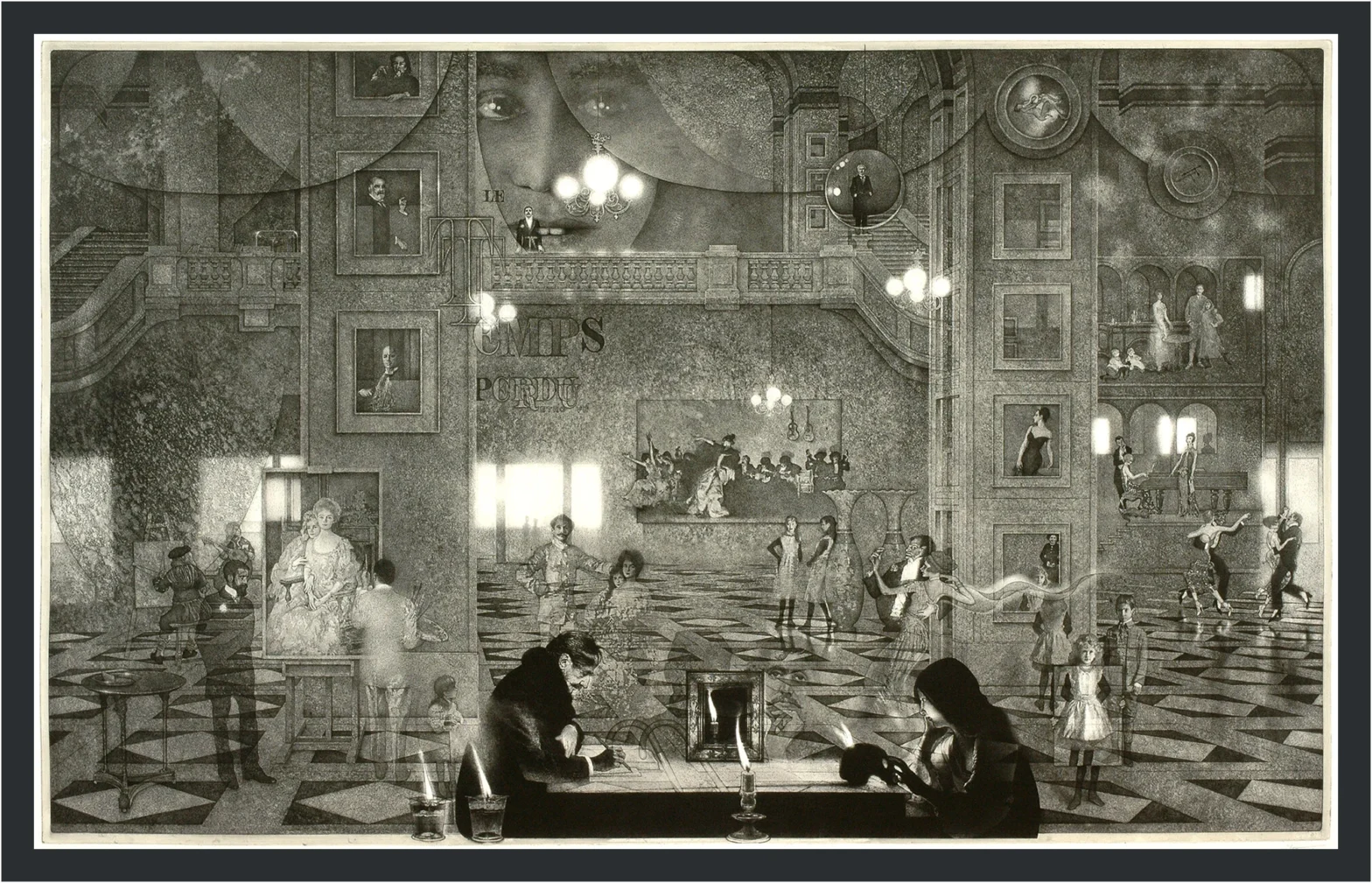

In his magnum opus, À La Recherche Du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time, 1913–1927) Marcel Proust posits that the “exquisite pleasure” of nostalgia can be generated by the most mundane of things—in the case of his narrative, the combination of madeleine crumbs and tea transporting the narrator back to his childhood. Might efforts to reclaim lost media from one’s childhood years be an attempt to capture that same “exquisite pleasure”, albeit with visual media in place of food and drink? However, while the nostalgia factor may go some way to explaining why certain lost content receives outsized attention within the community, it cannot entirely justify the impulse to seek such rarities. Very few of the missing episode-obsessed Doctor Who fans are old enough to have seen those lost serials on their initial broadcast; likewise, there are only a handful of people alive today who could have experienced Cleopatra or London After Midnight when they were first screened. Nostalgia, then, cannot be the sole motivator of this youth-centred interest in lost media.

Consider once again the Lost Media Wiki’s mission statement: “if it’s completely lost or simply inaccessible to the general public, it belongs here”. This is a perspective uniquely rooted in our current age of digital capitalism, where we anticipate access to media at the touch of a button. Compare this to Sandbrook’s comment that the concept of lost media is “unbelievably gutting. But actually even if it had existed, I wouldn’t have been able to see it anyway [as someone growing up in the pre-home media age], so that’s the kind of irony to it”. Via these contrasting viewpoints it is possible to discern a change in attitude regardingmedia consumption—whereas prior generations acknowledged the ephemerality of media, or more precisely their access to it, younger generations feel a sense of entitlement, fostered by the all-access economy of digital capitalism. Gone are the days of “the seventies”, as discussed by Sandbrook, when “they had absolutely no sense that this stuff had anything more than ephemeral value”. In our current context, in which every film and TV show is assumed to offer unimpeded and indefinite accessibility—and, therefore, an indefinite shelf-life—the prospect of unearthing lost media becomes all the more beguiling. The gaps in the archive show up all the more when the archive itself is flung open to the public.

Genuine lost media still attracts attention, and there are ongoing efforts in the UK by organisations like Film is Fabulous to catalogue to archives of elderly film collectors in the hope of retrieving rare material. Yet the definition of “lost” is rapidly changing—inexperienced posters on the r/lostmedia subreddit often complain about so-called lost films, only to be told that these films, while absent from streaming services, are purchasable onphysical media.

The strange case of Hoodwinked! is a prime example of this phenomenon. The Anne Hathaway animated fairy tale received poor reviews when it released in 2005, no doubt leading to its current obscurity. Although the film was in fact issued on DVD (and is readily available on torrenting sites), its absence from streaming services caused a minor panic on social media, with users demanding “Is Hoodwinked somehow lost media now? […] You can’t even buy a digital copy from iTunes, etc.”. Thus we can see that “lost media” has been reconfigured to mean “media which is not immediately accessible”, and it is this question of accessibility which remains central to contemporary discourse on the subject.

We now live in a world where food, products, and media can be obtained at the push of a button, often at very short notice. This has inevitably led to the development of an all-access mindset and its associated expectations—if X and Y are instantly available, why not Z? Indeed, the longing for Z is only emphasised by this unexpected frustration.

Thus we reach the central paradox of contemporary lost media discourse. Streaming and other forms of all-access capitalism have revolutionised our ability to consume media (and, through it, adverts, product placement, sponsorships, etc.), yet in some cases it is this same capitalist drive that caused media to become lost in the first place. From the silent films scrapped for their resalable silver content to the TV tapes junked due to their perceived lack of commercial value, the pursuit of profit has created a cultural problem (the loss of film and TV history) and, ironically, transformed it into service problem (the inability to meet the desires of consumers who now expect everything at a moment’s notice). The same economic system that encouraged the vandalism of culture as a cost-cutting measure has now created an insatiable appetite, particularly among those too young to remember a different world, for the one thing that it cannot sell us—a complete and unrestricted digital archive, and thus the films that are truly lost to time.