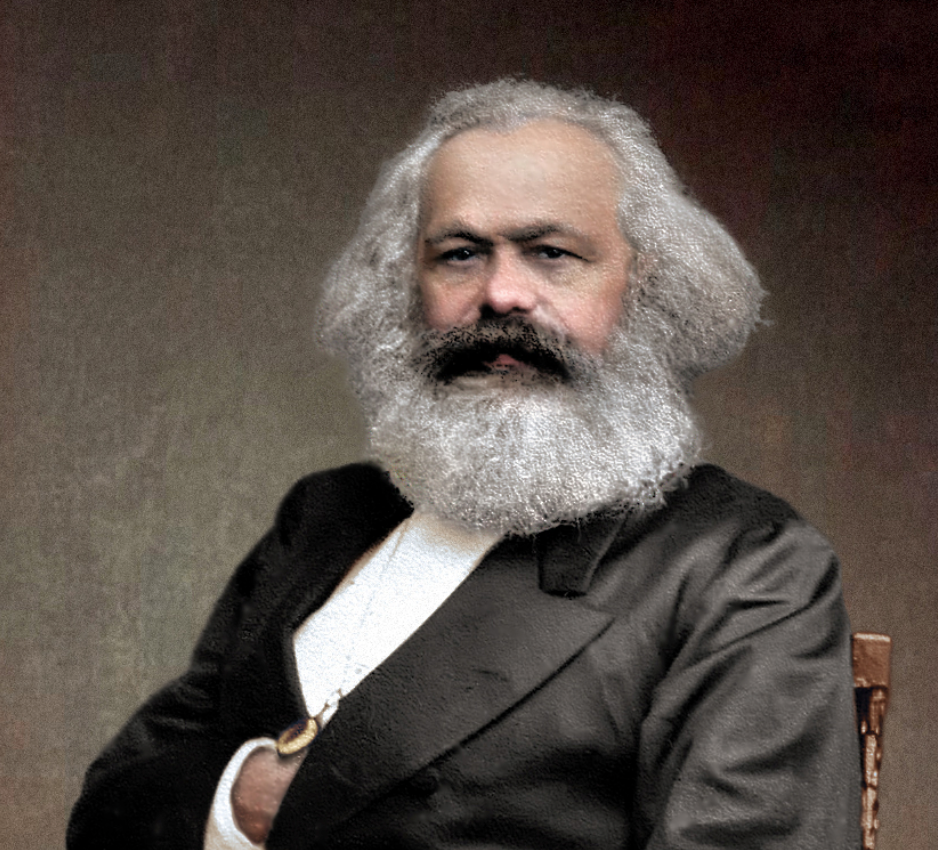

In 1845, Karl Marx declared: “philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it”.

Change it he did.

Political movements representing masses of new industrial workers, many inspired by his thought, reshaped the world in the 19th and 20th centuries through revolution and reform. His work influenced unions, labour parties and social democratic parties, and helped spark revolution via communist parties in Europe and beyond.

Around the world, “Marxist” governments were formed, who claimed to be committed to his principles, and who upheld dogmatic versions of his thought as part of their official doctrine.

Marx’s thought was groundbreaking. It came to stimulate arguments in every major language, in philosophy, history, politics and economics. It even helped to found the discipline of sociology.

Although his influence in the social sciences and humanities is not what it once was, his work continues to help theorists make sense of the complex social structures that shape our lives.

Marx was writing when mid-Victorian capitalism was at its Dickensian worst, analysing how the new industrialism was causing radical social upheaval and severe urban poverty. Of his many writings, perhaps the most well known and influential are the rather large Capital Volume 1 (1867) and the very small Communist Manifesto (1848), penned with his collaborator Frederick Engels.

On economics alone, he made important observations that influenced our understanding of the role of boom/bust cycles, the link between market competition and rapid technological advances, and the tendency of markets towards concentration and monopolies.

Marx also made prescient observations regarding what we now call “globalisation”. He emphasised “the newly created connections […] of the world market” and the important role of international trade.

At the time, property owners held the vast majority of wealth, and their wealth rapidly accumulated through the creation of factories.

The labour of the workers – the property-less masses – was bought and sold like any other commodity. The workers toiled for starvation wages, as “appendages of the machine[s]”, in Marx’s famous phrase. By holding them in this position, the owners grew ever richer, siphoning off the value created by this labour.

This would inevitably lead to militant international political organisation in response.

It is from this we get Marx’s famous call in 1848, the year of Europe-wide revolutions:

workers of the world unite!

To do philosophy properly, Marx thought, we have to form theories that capture the concrete details of real people’s lives – to make theory fully grounded in practice.

His primary interest wasn’t simply capitalism. It was human existence and our potential.

His enduring philosophical contribution is an insightful, historically grounded perspective on human beings and industrial society.

Marx observed capitalism wasn’t only an economic system by which we produced food, clothing and shelter; it was also bound up with a system of social relations.

Work structured people’s lives and opportunities in different ways depending on their role in the production process: most people were either part of the “owning class” or “working class”. The interests of these classes were fundamentally opposed, which led inevitably to conflict between them.

On the basis of this, Marx predicted the inevitable collapse of capitalism leading to equally inevitable working-class revolutions. However, he seriously underestimated capitalism’s adaptability. In particular, the way that parliamentary democracy and the welfare state could moderate the excesses and instabilities of the economic system.

Marx argued social change is driven by the tension created within an existing social order through technological and organisational innovations in production.

Technology-driven changes in production make new social forms possible, such that old social forms and classes become outmoded and displaced by new ones. Once, the dominant class were the land owning lords. But the new industrial system produced a new dominant class: the capitalists.

Against the philosophical trend to view human beings as simply organic machines, Marx saw us as a creative and productive type of being. Humanity uses these capacities to transform the natural world. However, in doing this we also, throughout history, transform ourselves in the process. This makes human life distinct from that of other animals.

The conditions under which people live deeply shape the way they see and understand the world. As Marx put it:

men make their own history [but] they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves.

Marx viewed human history as process of people progressively overcoming impediments to self-understanding and freedom. These impediments can be mental, material and institutional. He believed philosophy could offer ways we might realise our human potential in the world.

Theories, he said, were not just about “interpreting the world”, but “changing it”.

Individuals and groups are situated in social contexts inherited from the past which limit what they can do – but these social contexts afford us certain possibilities.

The present political situation that confronts us and the scope for actions we might take to improve it, is the result of our being situated in our unique place and time in history.

This approach has influenced thinkers across traditions and continents to better understand the complexities of the social and political world, and to think more concretely about prospects for change.

On the basis of his historical approach, Marx argued inequality is not a natural fact; it is socially created. He sought to show how economic systems such as feudalism or capitalism – despite being hugely complex historical developments – were ultimately our own creations.

By seeing the economic system and what it produces as objective and independent of humanity, this system comes to dominate us. When systematic exploitation is viewed as a product of the “natural order”, humans are, from a philosophical perspective, “enslaved” by their own creation.

What we have produced comes to be viewed as alien to us. Marx called this process “alienation”.

Despite having intrinsic creative capacities, most of humanity experience themselves as stifled by the conditions in which they work and live. They are alienated a) in the production process (“what” is produced and “how”); b) from others (with whom they constantly compete); and c) from their own creative potential.

For Marx, human beings intrinsically strive toward freedom, and we are not really free unless we control our own destiny.

Marx believed a rational social order could realise our human capacities as individuals as well as collectively, overcoming political and economic inequalities.

Writing in a period before workers could even vote (as voting was restricted to landowning males) Marx argued “the full and free development of every individual” – along with meaningful participation in the decisions that shaped their lives – would be realised through the creation of a “classless society [of] the free and equal”.

Marx’s concept of ideology introduced an innovative way to critique how dominant beliefs and practices – commonly taken to be for the good of all – actually reflect the interests and reinforce the power of the “ruling” class.

For Marx, beliefs in philosophy, culture and economics often function to rationalise unfair advantages and privileges as “natural” when, in fact, the amount of change we see in history shows they are not.

He was not saying this is a conspiracy of the ruling class, where those in the dominant class believe things simply because they reinforce the present power structure.

Rather, it is because people are raised and learn how to think within a given social order. Through this, the views that seem eminently rational rather conveniently tend to uphold the distribution of power and wealth as they are.

Marx had always aspired to be a philosopher, but was unable to pursue it as a profession because his views were judged too radical for a university post in his native Prussia. Instead, he earned his living as a crusading journalist.

By any account, Marx was a giant of modern thought.